Chapter 4: Deontology — Duty and Moral Law

Introduction

Is morality just all about happiness and pleasure? One essential ingredient to discussions about morality is the notion that morality entails having duties and obligations. Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) thought that in order to be moral, we need to follow rules or maxims which, when discovered by the use of reason, can guide us to rationally grounded answers about what we ought to do. Kant calls such maxims categorical imperatives, and they are distinct from hypothetical imperatives (Kant 2017).

– HUNTER AIKEN

Hypothetical imperatives are moral claims that take the shape of ‘if you want x, then you need to do y.’ For instance, ‘if you want to maximize the happiness of the greatest number of people, then you are morally obligated to do the action which would do so.’ Under hypothetical imperatives, there are a number of different outcomes in which the happiness of the greatest number could be satisfied (Kant 2017).

On the other hand, there are some moral claims that are absolute commands. They make moral claims to which there are no exceptions to the rule, and the outcome is irrelevant to the moral standing of the action. These are called categorical imperatives. There are two different kinds of categorical imperatives that Kant (2017) lists:

- To ‘act according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.’

- To never treat persons and others as mere means to an end, but treat them as ends in themselves.

Frankena questions the status of these maxims: “they might be necessary, but are they sufficient for determining what is actually moral and obligatory?” Frankena argues that there are some things which would satisfy the criteria of Kant’s maxims, but it does not mean that its the morally right thing to do. It also depends on the moral point of view from which we make moral laws from. Is our moral point of view to protect our own self-interests? Or is it from the point of view of genuine concern for well-being (Frankena 1973)?

In contrast, Ursula K. LeGuin walks us through a world of morality that is an inversion of the Kantian version. In the world of Omelas, no one appears to adhere to the Kantian system of morality, and they are much more attuned to the vision of utilitarianism. Is a world where everyone is happy worth the incredible suffering of one person? LeGuin prompts us to take the second categorical imperative much more seriously as she walks us through the world of Omelas (LeGuin 1973).

Reading 1: Immanuel Kant — “Duty Ethics”

PREFACE

. . . As my concern here is with moral philosophy, I limit the question suggested to this: Whether it is not of the utmost necessity to construct a pure thing which is only empirical and which belongs to anthropology? for that such a philosophy must be possible is evident from the common idea of duty and of the moral laws. Everyone must admit that if a law is to have moral force, i.e., to be the basis of an obligation, it must carry with it absolute necessity; that, for example, the precept, “Thou shalt not lie,” is not valid for men alone, as if other rational beings had no need to observe it; and so with all the other moral laws properly so called; that, therefore, the basis of obligation must not be sought in the nature of man, or in the circumstances in the world in which he is placed, but a priori simply in the conception of pure reason; and although any other precept which is founded on principles of mere experience may be in certain respects universal, yet in as far as it rests even in the least degree on an empirical basis, perhaps only as to a motive, such a precept, while it may be a practical rule, can never be called a moral law. . . .

FIRST SECTION—TRANSITION FROM THE COMMON RATIONAL KNOWLEDGE OF MORALITY TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL

Nothing can possibly be conceived in the world, or even out of it, which can be called good, without qualification, except a good will. Intelligence, wit, judgement, and the other talents of the mind, however they may be named, or courage, resolution, perseverance, as qualities of temperament, are undoubtedly good and desirable in many respects; but these gifts of nature may also become extremely bad and mischievous if the will which is to make use of them, and which, therefore, constitutes what is called character, is not good. It is the same with the gifts of fortune. Power, riches, honour, even health, and the general well-being and contentment with one’s condition which is called happiness, inspire pride, and often presumption, if there is not a good will to correct the influence of these on the mind, and with this also to rectify the whole principle of acting and adapt it to its end. The sight of a being who is not adorned with a single feature of a pure and good will, enjoying unbroken prosperity, can never give pleasure to an impartial rational spectator. Thus a good will appears to constitute the indispensable condition even of being worthy of happiness.

There are even some qualities which are of service to this good will itself and may facilitate its action, yet which have no intrinsic unconditional value, but always presuppose a good will, and this qualifies the esteem that we justly have for them and does not permit us to regard them as absolutely good. Moderation in the affections and passions, self-control, and calm deliberation are not only good in many respects, but even seem to constitute part of the intrinsic worth of the person; but they are far from deserving to be called good without qualification, although they have been so unconditionally praised by the ancients. For without the principles of a good will, they may become extremely bad, and the coolness of a villain not only makes him far more dangerous, but also directly makes him more abominable in our eyes than he would have been without it.

A good will is good not because of what it performs or effects, not by its aptness for the attainment of some proposed end, but simply by virtue of the volition; that is, it is good in itself, and considered by itself is to be esteemed much higher than all that can be brought about by it in favour of any inclination, nay even of the sum total of all inclinations. Even if it should happen that, owing to special disfavour of fortune, or the niggardly provision of a step-motherly nature, this will should wholly lack power to accomplish its purpose, if with its greatest efforts it should yet achieve nothing, and there should remain only the good will (not, to be sure, a mere wish, but the summoning of all means in our power), then, like a jewel, it would still shine by its own light, as a thing which has its whole value in itself. Its usefulness or fruitlessness can neither add nor take away anything from this value. It would be, as it were, only the setting to enable us to handle it the more conveniently in common commerce, or to attract to it the attention of those who are not yet connoisseurs, but not to recommend it to true connoisseurs, or to determine its value.

There is, however, something so strange in this idea of the absolute value of the mere will, in which no account is taken of its utility, that notwithstanding the thorough assent of even common reason to the idea, yet a suspicion must arise that it may perhaps really be the product of mere high-flown fancy, and that we may have misunderstood the purpose of nature in assigning reason as the governor of our will. Therefore we will examine this idea from this point of view.

In the physical constitution of an organized being, that is, a being adapted suitably to the purposes of life, we assume it as a fundamental principle that no organ for any purpose will be found but what is also the fittest and best adapted for that purpose. Now in a being which has reason and a will, if the proper object of nature were its conservation, its welfare, in a word, its happiness, then nature would have hit upon a very bad arrangement in selecting the reason of the creature to carry out this purpose. For all the actions which the creature has to perform with a view to this purpose, and the whole rule of its conduct, would be far more surely prescribed to it by instinct, and that end would have been attained thereby much more certainly than it ever can be by reason. Should reason have been communicated to this favoured creature over and above, it must only have served it to contemplate the happy constitution of its nature, to admire it, to congratulate itself thereon, and to feel thankful for it to the beneficent cause, but not that it should subject its desires to that weak and delusive guidance and meddle bunglingly with the purpose of nature. In a word, nature would have taken care that reason should not break forth into practical exercise, nor have the presumption, with its weak insight, to think out for itself the plan of happiness, and of the means of attaining it. Nature would not only have taken on herself the choice of the ends, but also of the means, and with wise foresight would have entrusted both to instinct.

And, in fact, we find that the more a cultivated reason applies itself with deliberate purpose to the enjoyment of life and happiness, so much the more does the man fail of true satisfaction. And from this circumstance there arises in many, if they are candid enough to confess it, a certain degree of misology, that is, hatred of reason, especially in the case of those who are most experienced in the use of it, because after calculating all the advantages they derive, I do not say from the invention of all the arts of common luxury, but even from the sciences (which seem to them to be after all only a luxury of the understanding), they find that they have, in fact, only brought more trouble on their shoulders, rather than gained in happiness; and they end by envying, rather than despising, the more common stamp of men who keep closer to the guidance of mere instinct and do not allow their reason much influence on their conduct. And this we must admit, that the judgement of those who would very much lower the lofty eulogies of the advantages which reason gives us in regard to the happiness and satisfaction of life, or who would even reduce them below zero, is by no means morose or ungrateful to the goodness with which the world is governed, but that there lies at the root of these judgements the idea that our existence has a different and far nobler end, for which, and not for happiness, reason is properly intended, and which must, therefore, be regarded as the supreme condition to which the private ends of man must, for the most part, be postponed.

For as reason is not competent to guide the will with certainty in regard to its objects and the satisfaction of all our wants (which it to some extent even multiplies), this being an end to which an implanted instinct would have led with much greater certainty; and since, nevertheless, reason is imparted to us as a practical faculty, i.e., as one which is to have influence on the will, therefore, admitting that nature generally in the distribution of her capacities has adapted the means to the end, its true destination must be to produce a will, not merely good as a means to something else, but good in itself, for which reason was absolutely necessary. This will then, though not indeed the sole and complete good, must be the supreme good and the condition of every other, even of the desire of happiness. Under these circumstances, there is nothing inconsistent with the wisdom of nature in the fact that the cultivation of the reason, which is requisite for the first and unconditional purpose, does in many ways interfere, at least in this life, with the attainment of the second, which is always conditional, namely, happiness. Nay, it may even reduce it to nothing, without nature thereby failing of her purpose. For reason recognizes the establishment of a good will as its highest practical destination, and in attaining this purpose is capable only of a satisfaction of its own proper kind, namely that from the attainment of an end, which end again is determined by reason only, notwithstanding that this may involve many a disappointment to the ends of inclination.

We have then to develop the notion of a will which deserves to be highly esteemed for itself and is good without a view to anything further, a notion which exists already in the sound natural understanding, requiring rather to be cleared up than to be taught, and which in estimating the value of our actions always takes the first place and constitutes the condition of all the rest. In order to do this, we will take the notion of duty, which includes that of a good will, although implying certain subjective restrictions and hindrances. These, however, far from concealing it, or rendering it unrecognizable, rather bring it out by contrast and make it shine forth so much the brighter.

I omit here all actions which are already recognized as inconsistent with duty, although they may be useful for this or that purpose, for with these the question whether they are done from duty cannot arise at all, since they even conflict with it. I also set aside those actions which really conform to duty, but to which men have no direct inclination, performing them because they are impelled thereto by some other inclination. For in this case we can readily distinguish whether the action which agrees with duty is done from duty, or from a selfish view. It is much harder to make this distinction when the action accords with duty and the subject has besides a direct inclination to it. For example, it is always a matter of duty that a dealer should not over charge an inexperienced purchaser; and wherever there is much commerce the prudent tradesman does not overcharge, but keeps a fixed price for everyone, so that a child buys of him as well as any other. Men are thus honestly served; but this is not enough to make us believe that the tradesman has so acted from duty and from principles of honesty: his own advantage required it; it is out of the question in this case to suppose that he might besides have a direct inclination in favour of the buyers, so that, as it were, from love he should give no advantage to one over another. Accordingly the action was done neither from duty nor from direct inclination, but merely with a selfish view.

On the other hand, it is a duty to maintain one’s life; and, in addition, everyone has also a direct inclination to do so. But on this account the often anxious care which most men take for it has no intrinsic worth, and their maxim has no moral import. They preserve their life as duty requires, no doubt, but not because duty requires. On the other hand, if adversity and hopeless sorrow have completely taken away the relish for life; if the unfortunate one, strong in mind, indignant at his fate rather than desponding or dejected, wishes for death, and yet preserves his life without loving it- not from inclination or fear, but from duty- then his maxim has a moral worth.

To be beneficent when we can is a duty; and besides this, there are many minds so sympathetically constituted that, without any other motive of vanity or self-interest, they find a pleasure in spreading joy around them and can take delight in the satisfaction of others so far as it is their own work. But I maintain that in such a case an action of this kind, however proper, however amiable it may be, has nevertheless no true moral worth, but is on a level with other inclinations, e.g., the inclination to honour, which, if it is happily directed to that which is in fact of public utility and accordant with duty and consequently honourable, deserves praise and encouragement, but not esteem. For the maxim lacks the moral import, namely, that such actions be done from duty, not from inclination. Put the case that the mind of that philanthropist were clouded by sorrow of his own, extinguishing all sympathy with the lot of others, and that, while he still has the power to benefit others in distress, he is not touched by their trouble because he is absorbed with his own; and now suppose that he tears himself out of this dead insensibility, and performs the action without any inclination to it, but simply from duty, then first has his action its genuine moral worth. Further still; if nature has put little sympathy in the heart of this or that man; if he, supposed to be an upright man, is by temperament cold and indifferent to the sufferings of others, perhaps because in respect of his own he is provided with the special gift of patience and fortitude and supposes, or even requires, that others should have the same- and such a man would certainly not be the meanest product of nature- but if nature had not specially framed him for a philanthropist, would he not still find in himself a source from whence to give himself a far higher worth than that of a good-natured temperament could be? Unquestionably. It is just in this that the moral worth of the character is brought out which is incomparably the highest of all, namely, that he is beneficent, not from inclination, but from duty.

To secure one’s own happiness is a duty, at least indirectly; for discontent with one’s condition, under a pressure of many anxieties and amidst unsatisfied wants, might easily become a great temptation to transgression of duty. But here again, without looking to duty, all men have already the strongest and most intimate inclination to happiness, because it is just in this idea that all inclinations are combined in one total. But the precept of happiness is often of such a sort that it greatly interferes with some inclinations, and yet a man cannot form any definite and certain conception of the sum of satisfaction of all of them which is called happiness. It is not then to be wondered at that a single inclination, definite both as to what it promises and as to the time within which it can be gratified, is often able to overcome such a fluctuating idea, and that a gouty patient, for instance, can choose to enjoy what he likes, and to suffer what he may, since, according to his calculation, on this occasion at least, he has not sacrificed the enjoyment of the present moment to a possibly mistaken expectation of a happiness which is supposed to be found in health. But even in this case, if the general desire for happiness did not influence his will, and supposing that in his particular case health was not a necessary element in this calculation, there yet remains in this, as in all other cases, this law, namely, that he should promote his happiness not from inclination but from duty, and by this would his conduct first acquire true moral worth.

It is in this manner, undoubtedly, that we are to understand those passages of Scripture also in which we are commanded to love our neighbour, even our enemy. For love, as an affection, cannot be commanded, but beneficence for duty’s sake may; even though we are not impelled to it by any inclination- nay, are even repelled by a natural and unconquerable aversion. This is practical love and not pathological- a love which is seated in the will, and not in the propensions of sense- in principles of action and not of tender sympathy; and it is this love alone which can be commanded.

The second proposition is: That an action done from duty derives its moral worth, not from the purpose which is to be attained by it, but from the maxim by which it is determined, and therefore does not depend on the realization of the object of the action, but merely on the principle of volition by which the action has taken place, without regard to any object of desire. It is clear from what precedes that the purposes which we may have in view in our actions, or their effects regarded as ends and springs of the will, cannot give to actions any unconditional or moral worth. In what, then, can their worth lie, if it is not to consist in the will and in reference to its expected effect? It cannot lie anywhere but in the principle of the will without regard to the ends which can be attained by the action. For the will stands between its a priori principle, which is formal, and its a posteriori spring, which is material, as between two roads, and as it must be determined by something, it follows that it must be determined by the formal principle of volition when an action is done from duty, in which case every material principle has been withdrawn from it.

The third proposition, which is a consequence of the two preceding, I would express thus: Duty is the necessity of acting from respect for the law. I may have inclination for an object as the effect of my proposed action, but I cannot have respect for it, just for this reason, that it is an effect and not an energy of will. Similarly I cannot have respect for inclination, whether my own or another’s; I can at most, if my own, approve it; if another’s, sometimes even love it; i.e., look on it as favourable to my own interest. It is only what is connected with my will as a principle, by no means as an effect- what does not subserve my inclination, but overpowers it, or at least in case of choice excludes it from its calculation- in other words, simply the law of itself, which can be an object of respect, and hence a command. Now an action done from duty must wholly exclude the influence of inclination and with it every object of the will, so that nothing remains which can determine the will except objectively the law, and subjectively pure respect for this practical law, and consequently the maxim * that I should follow this law even to the thwarting of all my inclinations.

* A maxim is the subjective principle of volition. The objective principle (i.e., that which would also serve subjectively as a practical principle to all rational beings if reason had full power over the faculty of desire) is the practical law.

Thus the moral worth of an action does not lie in the effect expected from it, nor in any principle of action which requires to borrow its motive from this expected effect. For all these effects- agreeableness of one’s condition and even the promotion of the happiness of others- could have been also brought about by other causes, so that for this there would have been no need of the will of a rational being; whereas it is in this alone that the supreme and unconditional good can be found. The pre-eminent good which we call moral can therefore consist in nothing else than the conception of law in itself, which certainly is only possible in a rational being, in so far as this conception, and not the expected effect, determines the will. This is a good which is already present in the person who acts accordingly, and we have not to wait for it to appear first in the result. *

* It might be here objected to me that I take refuge behind the word respect in an obscure feeling, instead of giving a distinct solution of the question by a concept of the reason. But although respect is a feeling, it is not a feeling received through influence, but is self-wrought by a rational concept, and, therefore, is specifically distinct from all feelings of the former kind, which may be referred either to inclination or fear, What I recognise immediately as a law for me, I recognise with respect. This merely signifies the consciousness that my will is subordinate to a law, without the intervention of other influences on my sense. The immediate determination of the will by the law, and the consciousness of this, is called respect, so that this is regarded as an effect of the law on the subject, and not as the cause of it. Respect is properly the conception of a worth which thwarts my self-love. Accordingly it is something which is considered neither as an object of inclination nor of fear, although it has something analogous to both. The object of respect is the law only, and that the law which we impose on ourselves and yet recognise as necessary in itself. As a law, we are subjected too it without consulting self-love; as imposed by us on ourselves, it is a result of our will. In the former aspect it has an analogy to fear, in the latter to inclination. Respect for a person is properly only respect for the law (of honesty, etc.) of which he gives us an example. Since we also look on the improvement of our talents as a duty, we consider that we see in a person of talents, as it were, the example of a law (viz., to become like him in this by exercise), and this constitutes our respect. All so-called moral interest consists simply in respect for the law.

But what sort of law can that be, the conception of which must determine the will, even without paying any regard to the effect expected from it, in order that this will may be called good absolutely and without qualification? As I have deprived the will of every impulse which could arise to it from obedience to any law, there remains nothing but the universal conformity of its actions to law in general, which alone is to serve the will as a principle, i.e., I am never to act otherwise than so that I could also will that my maxim should become a universal law. Here, now, it is the simple conformity to law in general, without assuming any particular law applicable to certain actions, that serves the will as its principle and must so serve it, if duty is not to be a vain delusion and a chimerical notion. The common reason of men in its practical judgements perfectly coincides with this and always has in view the principle here suggested. Let the question be, for example: May I when in distress make a promise with the intention not to keep it? I readily distinguish here between the two significations which the question may have: Whether it is prudent, or whether it is right, to make a false promise? The former may undoubtedly often be the case. I see clearly indeed that it is not enough to extricate myself from a present difficulty by means of this subterfuge, but it must be well considered whether there may not hereafter spring from this lie much greater inconvenience than that from which I now free myself, and as, with all my supposed cunning, the consequences cannot be so easily foreseen but that credit once lost may be much more injurious to me than any mischief which I seek to avoid at present, it should be considered whether it would not be more prudent to act herein according to a universal maxim and to make it a habit to promise nothing except with the intention of keeping it. But it is soon clear to me that such a maxim will still only be based on the fear of consequences. Now it is a wholly different thing to be truthful from duty and to be so from apprehension of injurious consequences. In the first case, the very notion of the action already implies a law for me; in the second case, I must first look about elsewhere to see what results may be combined with it which would affect myself. For to deviate from the principle of duty is beyond all doubt wicked; but to be unfaithful to my maxim of prudence may often be very advantageous to me, although to abide by it is certainly safer. The shortest way, however, and an unerring one, to discover the answer to this question whether a lying promise is consistent with duty, is to ask myself, “Should I be content that my maxim (to extricate myself from difficulty by a false promise) should hold good as a universal law, for myself as well as for others?” and should I be able to say to myself, “Every one may make a deceitful promise when he finds himself in a difficulty from which he cannot otherwise extricate himself?” Then I presently become aware that while I can will the lie, I can by no means will that lying should be a universal law. For with such a law there would be no promises at all, since it would be in vain to allege my intention in regard to my future actions to those who would not believe this allegation, or if they over hastily did so would pay me back in my own coin. Hence my maxim, as soon as it should be made a universal law, would necessarily destroy itself.

I do not, therefore, need any far-reaching penetration to discern what I have to do in order that my will may be morally good. Inexperienced in the course of the world, incapable of being prepared for all its contingencies, I only ask myself: Canst thou also will that thy maxim should be a universal law? If not, then it must be rejected, and that not because of a disadvantage accruing from it to myself or even to others, but because it cannot enter as a principle into a possible universal legislation, and reason extorts from me immediate respect for such legislation. I do not indeed as yet discern on what this respect is based (this the philosopher may inquire), but at least I understand this, that it is an estimation of the worth which far outweighs all worth of what is recommended by inclination, and that the necessity of acting from pure respect for the practical law is what constitutes duty, to which every other motive must give place, because it is the condition of a will being good in itself, and the worth of such a will is above everything.

Thus, then, without quitting the moral knowledge of common human reason, we have arrived at its principle. And although, no doubt, common men do not conceive it in such an abstract and universal form, yet they always have it really before their eyes and use it as the standard of their decision. . . .

Nor could anything be more fatal to morality than that we should wish to derive it from examples. For every example of it that is set before me must be first itself tested by principles of morality, whether it is worthy to serve as an original example, i.e., as a pattern; but by no means can it authoritatively furnish the conception of morality. Even the Holy One of the Gospels must first be compared with our ideal of moral perfection before we can recognise Him as such; and so He says of Himself, “Why call ye Me (whom you see) good; none is good (the model of good) but God only (whom ye do not see)?” But whence have we the conception of God as the supreme good? Simply from the idea of moral perfection, which reason frames a priori and connects inseparably with the notion of a free will. Imitation finds no place at all in morality, and examples serve only for encouragement, i.e., they put beyond doubt the feasibility of what the law commands, they make visible that which the practical rule expresses more generally, but they can never authorize us to set aside the true original which lies in reason and to guide ourselves by examples. . . .

From what has been said, it is clear that all moral conceptions have their seat and origin completely a priori in the reason, and that, moreover, in the commonest reason just as truly as in that which is in the highest degree speculative; that they cannot be obtained by abstraction from any empirical, and therefore merely contingent, knowledge; that it is just this purity of their origin that makes them worthy to serve as our supreme practical principle, and that just in proportion as we add anything empirical, we detract from their genuine influence and from the absolute value of actions; that it is not only of the greatest necessity, in a purely speculative point of view, but is also of the greatest practical importance, to derive these notions and laws from pure reason, to present them pure and unmixed, and even to determine the compass of this practical or pure rational knowledge, i.e., to determine the whole faculty of pure practical reason; and, in doing so, we must not make its principles dependent on the particular nature of human reason, though in speculative philosophy this may be permitted, or may even at times be necessary; but since moral laws ought to hold good for every rational creature, we must derive them from the general concept of a rational being. In this way, although for its application to man morality has need of anthropology, yet, in the first instance, we must treat it independently as pure philosophy, i.e., as metaphysic, complete in itself (a thing which in such distinct branches of science is easily done); knowing well that unless we are in possession of this, it would not only be vain to determine the moral element of duty in right actions for purposes of speculative criticism, but it would be impossible to base morals on their genuine principles, even for common practical purposes, especially of moral instruction, so as to produce pure moral dispositions, and to engraft them on men’s minds to the promotion of the greatest possible good in the world. . . .

. . . [T]he question how the imperative of morality is possible, is undoubtedly one, the only one, demanding a solution, as this is not at all hypothetical, and the objective necessity which it presents cannot rest on any hypothesis, as is the case with the hypothetical imperatives. Only here we must never leave out of consideration that we cannot make out by any example, in other words empirically, whether there is such an imperative at all, but it is rather to be feared that all those which seem to be categorical may yet be at bottom hypothetical. For instance, when the precept is: “Thou shalt not promise deceitfully”; and it is assumed that the necessity of this is not a mere counsel to avoid some other evil, so that it should mean: “Thou shalt not make a lying promise, lest if it become known thou shouldst destroy thy credit,” but that an action of this kind must be regarded as evil in itself, so that the imperative of the prohibition is categorical; then we cannot show with certainty in any example that the will was determined merely by the law, without any other spring of action, although it may appear to be so. For it is always possible that fear of disgrace, perhaps also obscure dread of other dangers, may have a secret influence on the will. Who can prove by experience the non-existence of a cause when all that experience tells us is that we do not perceive it? But in such a case the so-called moral imperative, which as such appears to be categorical and unconditional, would in reality be only a pragmatic precept, drawing our attention to our own interests and merely teaching us to take these into consideration.

We shall therefore have to investigate a priori the possibility of a categorical imperative, as we have not in this case the advantage of its reality being given in experience, so that [the elucidation of] its possibility should be requisite only for its explanation, not for its establishment. In the meantime it may be discerned beforehand that the categorical imperative alone has the purport of a practical law; all the rest may indeed be called principles of the will but not laws, since whatever is only necessary for the attainment of some arbitrary purpose may be considered as in itself contingent, and we can at any time be free from the precept if we give up the purpose; on the contrary, the unconditional command leaves the will no liberty to choose the opposite; consequently it alone carries with it that necessity which we require in a law.

Secondly, in the case of this categorical imperative or law of morality, the difficulty (of discerning its possibility) is a very profound one. It is an a priori synthetical practical proposition; * and as there is so much difficulty in discerning the possibility of speculative propositions of this kind, it may readily be supposed that the difficulty will be no less with the practical.

* I connect the act with the will without presupposing any condition resulting from any inclination, but a priori, and therefore necessarily (though only objectively, i.e., assuming the idea of a reason possessing full power over all subjective motives). This is accordingly a practical proposition which does not deduce the willing of an action by mere analysis from another already presupposed (for we have not such a perfect will), but connects it immediately with the conception of the will of a rational being, as something not contained in it.

In this problem we will first inquire whether the mere conception of a categorical imperative may not perhaps supply us also with the formula of it, containing the proposition which alone can be a categorical imperative; for even if we know the tenor of such an absolute command, yet how it is possible will require further special and laborious study, which we postpone to the last section.

When I conceive a hypothetical imperative, in general I do not know beforehand what it will contain until I am given the condition. But when I conceive a categorical imperative, I know at once what it contains. For as the imperative contains besides the law only the necessity that the maxims * shall conform to this law, while the law contains no conditions restricting it, there remains nothing but the general statement that the maxim of the action should conform to a universal law, and it is this conformity alone that the imperative properly represents as necessary.

* A maxim is a subjective principle of action, and must be distinguished from the objective principle, namely, practical law. The former contains the practical rule set by reason according to the conditions of the subject (often its ignorance or its inclinations), so that it is the principle on which the subject acts; but the law is the objective principle valid for every rational being, and is the principle on which it ought to act that is an imperative.

There is therefore but one categorical imperative, namely, this: Act only on that maxim whereby thou canst at the same time will that it should become a universal law.

Now if all imperatives of duty can be deduced from this one imperative as from their principle, then, although it should remain undecided what is called duty is not merely a vain notion, yet at least we shall be able to show what we understand by it and what this notion means.

Since the universality of the law according to which effects are produced constitutes what is properly called nature in the most general sense (as to form), that is the existence of things so far as it is determined by general laws, the imperative of duty may be expressed thus: Act as if the maxim of thy action were to become by thy will a universal law of nature.

We will now enumerate a few duties, adopting the usual division of them into duties to ourselves and ourselves and to others, and into perfect and imperfect duties. *

* It must be noted here that I reserve the division of duties for a future metaphysic of morals; so that I give it here only as an arbitrary one (in order to arrange my examples). For the rest, I understand by a perfect duty one that admits no exception in favour of inclination and then I have not merely external but also internal perfect duties. This is contrary to the use of the word adopted in the schools; but I do not intend to justify there, as it is all one for my purpose whether it is admitted or not.

- A man reduced to despair by a series of misfortunes feels wearied of life, but is still so far in possession of his reason that he can ask himself whether it would not be contrary to his duty to himself to take his own life. Now he inquires whether the maxim of his action could become a universal law of nature. His maxim is: “From self-love I adopt it as a principle to shorten my life when its longer duration is likely to bring more evil than satisfaction.” It is asked then simply whether this principle founded on self-love can become a universal law of nature. Now we see at once that a system of nature of which it should be a law to destroy life by means of the very feeling whose special nature it is to impel to the improvement of life would contradict itself and, therefore, could not exist as a system of nature; hence that maxim cannot possibly exist as a universal law of nature and, consequently, would be wholly inconsistent with the supreme principle of all duty.

- Another finds himself forced by necessity to borrow money. He knows that he will not be able to repay it, but sees also that nothing will be lent to him unless he promises stoutly to repay it in a definite time. He desires to make this promise, but he has still so much conscience as to ask himself: “Is it not unlawful and inconsistent with duty to get out of a difficulty in this way?” Suppose however that he resolves to do so: then the maxim of his action would be expressed thus: “When I think myself in want of money, I will borrow money and promise to repay it, although I know that I never can do so.” Now this principle of self-love or of one’s own advantage may perhaps be consistent with my whole future welfare; but the question now is, “Is it right?” I change then the suggestion of self-love into a universal law, and state the question thus: “How would it be if my maxim were a universal law?” Then I see at once that it could never hold as a universal law of nature, but would necessarily contradict itself. For supposing it to be a universal law that everyone when he thinks himself in a difficulty should be able to promise whatever he pleases, with the purpose of not keeping his promise, the promise itself would become impossible, as well as the end that one might have in view in it, since no one would consider that anything was promised to him, but would ridicule all such statements as vain pretences.

- A third finds in himself a talent which with the help of some culture might make him a useful man in many respects. But he finds himself in comfortable circumstances and prefers to indulge in pleasure rather than to take pains in enlarging and improving his happy natural capacities. He asks, however, whether his maxim of neglect of his natural gifts, besides agreeing with his inclination to indulgence, agrees also with what is called duty. He sees then that a system of nature could indeed subsist with such a universal law although men (like the South Sea islanders) should let their talents rest and resolve to devote their lives merely to idleness, amusement, and propagation of their species- in a word, to enjoyment; but he cannot possibly will that this should be a universal law of nature, or be implanted in us as such by a natural instinct. For, as a rational being, he necessarily wills that his faculties be developed, since they serve him and have been given him, for all sorts of possible purposes.

- A fourth, who is in prosperity, while he sees that others have to contend with great wretchedness and that he could help them, thinks: “What concern is it of mine? Let everyone be as happy as Heaven pleases, or as he can make himself; I will take nothing from him nor even envy him, only I do not wish to contribute anything to his welfare or to his assistance in distress!” Now no doubt if such a mode of thinking were a universal law, the human race might very well subsist and doubtless even better than in a state in which everyone talks of sympathy and good-will, or even takes care occasionally to put it into practice, but, on the other side, also cheats when he can, betrays the rights of men, or otherwise violates them. But although it is possible that a universal law of nature might exist in accordance with that maxim, it is impossible to will that such a principle should have the universal validity of a law of nature. For a will which resolved this would contradict itself, inasmuch as many cases might occur in which one would have need of the love and sympathy of others, and in which, by such a law of nature, sprung from his own will, he would deprive himself of all hope of the aid he desires.

These are a few of the many actual duties, or at least what we regard as such, which obviously fall into two classes on the one principle that we have laid down. We must be able to will that a maxim of our action should be a universal law. This is the canon of the moral appreciation of the action generally. Some actions are of such a character that their maxim cannot without contradiction be even conceived as a universal law of nature, far from it being possible that we should will that it should be so. In others this intrinsic impossibility is not found, but still it is impossible to will that their maxim should be raised to the universality of a law of nature, since such a will would contradict itself It is easily seen that the former violate strict or rigorous (inflexible) duty; the latter only laxer (meritorious) duty. Thus it has been completely shown how all duties depend as regards the nature of the obligation (not the object of the action) on the same principle.

. . . Now I say: man and generally any rational being exists as an end in himself, not merely as a means to be arbitrarily used by this or that will, but in all his actions, whether they concern himself or other rational beings, must be always regarded at the same time as an end. All objects of the inclinations have only a conditional worth, for if the inclinations and the wants founded on them did not exist, then their object would be without value. But the inclinations, themselves being sources of want, are so far from having an absolute worth for which they should be desired that on the contrary it must be the universal wish of every rational being to be wholly free from them. Thus the worth of any object which is to be acquired by our action is always conditional. Beings whose existence depends not on our will but on nature’s, have nevertheless, if they are irrational beings, only a relative value as means, and are therefore called things; rational beings, on the contrary, are called persons, because their very nature points them out as ends in themselves, that is as something which must not be used merely as means, and so far therefore restricts freedom of action (and is an object of respect). These, therefore, are not merely subjective ends whose existence has a worth for us as an effect of our action, but objective ends, that is, things whose existence is an end in itself; an end moreover for which no other can be substituted, which they should subserve merely as means, for otherwise nothing whatever would possess absolute worth; but if all worth were conditioned and therefore contingent, then there would be no supreme practical principle of reason whatever.

If then there is a supreme practical principle or, in respect of the human will, a categorical imperative, it must be one which, being drawn from the conception of that which is necessarily an end for everyone because it is an end in itself, constitutes an objective principle of will, and can therefore serve as a universal practical law. The foundation of this principle is: rational nature exists as an end in itself. Man necessarily conceives his own existence as being so; so far then this is a subjective principle of human actions. But every other rational being regards its existence similarly, just on the same rational principle that holds for me: * so that it is at the same time an objective principle, from which as a supreme practical law all laws of the will must be capable of being deduced. Accordingly the practical imperative will be as follows: So act as to treat humanity, whether in thine own person or in that of any other, in every case as an end withal, never as means only. . . .

. . .Looking back now on all previous attempts to discover the principle of morality, we need not wonder why they all failed. It was seen that man was bound to laws by duty, but it was not observed that the laws to which he is subject are only those of his own giving, though at the same time they are universal, and that he is only bound to act in conformity with his own will; a will, however, which is designed by nature to give universal laws. For when one has conceived man only as subject to a law (no matter what), then this law required some interest, either by way of attraction or constraint, since it did not originate as a law from his own will, but this will was according to a law obliged by something else to act in a certain manner. Now by this necessary consequence all the labour spent in finding a supreme principle of duty was irrevocably lost. For men never elicited duty, but only a necessity of acting from a certain interest. Whether this interest was private or otherwise, in any case the imperative must be conditional and could not by any means be capable of being a moral command. I will therefore call this the principle of autonomy of the will, in contrast with every other which I accordingly reckon as heteronomy.

The conception of the will of every rational being as one which must consider itself as giving in all the maxims of its will universal laws, so as to judge itself and its actions from this point of view- this conception leads to another which depends on it and is very fruitful, namely that of a kingdom of ends.

By a kingdom I understand the union of different rational beings in a system by common laws. Now since it is by laws that ends are determined as regards their universal validity, hence, if we abstract from the personal differences of rational beings and likewise from all the content of their private ends, we shall be able to conceive all ends combined in a systematic whole (including both rational beings as ends in themselves, and also the special ends which each may propose to himself), that is to say, we can conceive a kingdom of ends, which on the preceding principles is possible.

For all rational beings come under the law that each of them must treat itself and all others never merely as means, but in every case at the same time as ends in themselves. Hence results a systematic union of rational being by common objective laws, i.e., a kingdom which may be called a kingdom of ends, since what these laws have in view is just the relation of these beings to one another as ends and means. . . .

This is an abridged version of Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysic of Morals by Immanuel Kant, translated by Thomas Kingsmill Abbott. The original work is in the public domain and available via Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/5682. Abridgment and adaptation by Grace Boehm, 2025. This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.

Contemporary Language Edition

Reading 2: Jenna Woodrow – “The Problem of Future Crimes”

The Time Traveler’s Dilemma presents a difficult moral question: If you could go back in time and kill Adolf Hitler before he committed any crimes, would it be the right thing to do? This thought experiment asks us to consider whether it is ever acceptable to harm an innocent person to prevent possible future harm. It challenges us to think about how we balance our moral rules with the outcomes of our actions, and whether knowing the future changes what we should do.

The Problem of Future Crimes

Imagine this:

You’re a time traveler from the 21st century. You’ve just arrived in Germany in the year 1923. You know from history that a struggling political agitator named Adolf Hitler will soon rise to power. Within two decades, he will become the dictator of Nazi Germany, start World War II, and be responsible for the deaths of tens of millions of people—including six million Jews in the Holocaust.

But in 1923, none of that has happened yet.

Right now, Hitler is just an angry ex-soldier with a small following and a lot of dangerous ideas. He hasn’t committed any large-scale crimes. Most people think of him as a loud, unstable fringe figure—someone who might just fade away.

And yet, you know better. You know that if no one stops him, catastrophic suffering will follow.

You have a rare chance. If you act now—quietly and efficiently—you could kill Hitler. You could prevent the war, the genocide, and the enormous loss of life. But you’d also be killing a person who hasn’t yet done anything to deserve it, and you’d be doing so with premeditated intent.

What should you do?

Bibliography

Kant, Immanuel. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. Translated and edited by Mary Gregor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. Originally published 1785.

Mill, John Stuart. Utilitarianism. 2nd ed. Edited by George Sher. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2001. Originally published 1863.

Walzer, Michael. “Political Action: The Problem of Dirty Hands.” Philosophy & Public Affairs 2, no. 2 (Winter 1973): 160–180. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2264975

Reading 3: Jenna Woodrow – “The Trolley Problem”

The Trolley Problem is a now-classic thought experiment in moral philosophy, originally introduced by Philippa Foot in 1967 to explore how we make ethical decisions involving harm and benefit. It poses a stark dilemma that asks whether it’s ever permissible to sacrifice one life to save several others. Philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson later expanded on the scenario, introducing new variations—such as the “fat man” version—that raise deeper questions about rights, moral intention, and the limits of ethical principles like duty and consent. These dilemmas have become central tools for testing the strengths and limits of ethical theories.

–Jenna Woodrow

The Trolley Problem

Imagine this:

You’re standing next to a set of train tracks when you suddenly notice something terrifying—a runaway trolley is speeding down the rails, completely out of control. Up ahead, five people are stuck on the track. They can’t move, and if the trolley continues on its path, it will hit and kill all five of them.

But you’re not powerless. You’re standing beside a lever that controls a track switch. If you pull the lever, the trolley will change tracks. There’s just one problem: on the other track, there’s one person who is also stuck and can’t move. If you pull the lever, you’ll save five lives, but the trolley will hit and kill the one person on the side track.

So you face a moral dilemma:

If you do nothing, the trolley will continue on its path and kill five people.

If you pull the lever, you will redirect the trolley, and only one person will die—but you will have actively caused that death.

What should you do?

Bibliography

Foot, Philippa. “The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of the Double Effect.” Oxford Review 5 (1967): 5–15.

Thomson, Judith Jarvis. “The Trolley Problem.” The Yale Law Journal 94, no. 6 (1985): 1395–1415. https://doi.org/10.2307/796133.

Reading 4: Onora O’Neill — “Kantian Approaches to Some Famine Problems”

Introduction

Relative to most other philosophers, Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) was a late bloomer, publishing his first significant work, The Critique of Pure Reason, in 1781 at age 57. But this did not slow him down, as through his 50s, 60s, and 70s, he published numerous large and influential works in many areas of philosophy, including ethics. He published two large works on ethics — The Critique of Practical Reason and The Metaphysics of Morals — but it is his first short work of ethics — Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals — that is his most important because it provides a succinct and relatively readable account of his ethics.

Some of the main questions that Kant’s ethics focuses on are questions of right and wrong:

- What makes an action right or wrong?

- Which actions are we required by morality to perform?

- Do consequences matter?

- Is it ever permissible to do something morally wrong in order to achieve good consequences?

- Is it important to do actions with good intentions? And what are good intentions?

Some of Kant’s answers to some of these questions are complex, but as we will see, he does not think that consequences matter, and thus, good consequences cannot justify wrong actions. He also thinks that intentions are important to the ethical evaluation of actions.

Further Reading: Joseph Kranak — “Kantian Deontology”

Deontology

One of the distinctive features of Kant’s ethics is that it focuses on duties, defined by right and wrong. Right and wrong (which are the primary deontic categories, along with obligatory, optional, supererogatory, and others) are distinct from good and bad (which are value categories) in that they directly prescribe actions: right actions are ones we ought to do (are morally required to do) and wrong actions we ought not to do (are morally forbidden from doing). This style of ethics is referred to as deontology. The name comes from the Greek word deon, meaning duty or obligation. In deontology, the deontic categories are primary, while value determinations are derived from them. As we will see, Kant believes all our duties can be derived from the categorical imperative. We will first need to explain what Kant means by the phrase “categorical imperative,” and then we will look at the content of this rule.

First, Kant believes that morality must be rational. He models his morality on science, which seeks to discover universal laws that govern the natural world. Similarly, morality will be a system of universal rules that govern action. In Kant’s view, as we will see, right action is ultimately a rational action. As an ethics of duty, Kant believes that ethics consist of commands about what we ought to do. The word “imperative” in his categorical imperative means a command or order. However, unlike most other commands, which usually come from some authority, these commands come from within, from our own reason. Still, they function the same way: they are commands to do certain actions.

Kant distinguishes two types of imperatives: hypothetical and categorical imperatives. A hypothetical imperative is a contingent command. It is conditional on a person’s wants, needs, or desires and normally comes in the following form: “If you want/need A, then you ought to do B.” For example, the advice “If you want to do well on a test, then you should study a lot” would be a hypothetical imperative. The command that you study is contingent on your desire to do well on the test. Other examples are, “If you are thirsty, drink water,” or “If you want to be in better shape, you should exercise.” Such commands are more like advice on how to accomplish our goals than moral rules. If you do not have a particular want, desire, or goal, then a hypothetical imperative does not apply. For example, if you do not want to be in better shape, then the hypothetical imperative that you should exercise, does not apply to you.

A genuinely moral imperative would not be contingent on wants, desires, or needs, and this is what is meant by a categorical imperative. A categorical imperative, instead of taking an if-then form, is an absolute command, such as “Do A” or “You ought to do A.” Examples of categorical imperatives would be “You should not kill,” “You ought to help those in need,” or “Do not steal.” It does not matter what your wants or goals are; you should follow a categorical imperative no matter what.

But these are not the categorical imperative. Kant believes that there is one categorical imperative that is the most important and that should guide all of our actions. This is the ultimate categorical imperative from which all other moral rules are derived. This categorical imperative can be expressed in several different ways, and Kant presents three formulations of it in The Groundwork.

The First Formulation of the Categorical Imperative

The underlying idea behind the first formulation of the categorical imperative is that moral rules are supposed to be universal laws. If we think of comparable laws — such as scientific laws, like the law of gravitational attraction or Newton’s three laws of motion — they are universal and apply to all people equally, no matter who they are or what their needs are. If our moral rules are to be rational, then they should have the same form.

From this idea, Kant derives his first formulation of the categorical imperative: “act only in accordance with that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it become a universal law” (Groundwork 4:421). [1]

First, we must explain the word “maxim.” What Kant means by a maxim is a personal rule or a general principle that underlies a particular action. As rational beings, we do not just act randomly; we devise certain rules that tell us what to do in different circumstances.

A complete maxim will include three pieces:

- The action

- The circumstances under which we do that action

- The purpose behind that action

For example, consider the maxim explaining why you are reading this book. If it is an assigned text, it might be, “I will read all books assigned for class because I want to succeed in class.” Different principles could underlie the same action. For example, you might be reading this book simply to help you understand the topic, in which case your principle might be, “When I am confused about a topic, I will read an accessible text to improve my understanding.” The important point is that we are guided by general principles that we give to ourselves, which tell us what we will do in certain circumstances.

Thus, the first formulation is a test of whether any particular maxim should be followed or not. We test a maxim by universalizing it; that is, by asking if it would be possible for everyone to live by this maxim. If the maxim can be universalized, meaning that it is possible that everyone could live by it, then it is permissible to follow it. If it cannot be universalized, then it is impermissible to follow it. The logic of the universalization test is that any rule you follow should apply to everyone — there is nothing special about you that allows you to be an exception.

To look at some examples, imagine you need money to pay off some debts. You go to a friend to borrow the money and tell this friend that you will pay him back. You know you will not be able to pay your friend back, but you promise him nonetheless. You are making a false promise. Is this permissible? To test, we first look at the maxim underlying the action, something like, “If I need something, I will make a false promise in order to get what I need.” What would happen if everyone were to make false promises every time they needed something? False promises would be rampant, so rampant that promises would become meaningless; they would just be empty words. For this reason, the maxim cannot be universalized. The maxim included the idea of making a promise, but if, when universalized, promises cease to have any meaning, then we could not really make a promise. Since the maxim cannot be universalized, we should not follow it, and thus, we derive the duty to not make false promises.

We should note that Kant’s universalization test is not asking whether universalizing a maxim would lead to undesirable consequences. Kant is not claiming that making a false promise is wrong because we would not want to live in a world where no one kept their promises. It is wrong because it is not possible to universalize the maxim. It is not possible because it leads to a contradiction. In this case, the contradiction is in the concept of a promise: that it becomes meaningless when universalized.

We can see this with other maxims. If you are thinking of stealing something, the maxim underlying this action might be something like, “I will steal the things I want so I can have what I want.” If everyone were to follow this maxim, then the concept of ownership would cease to have any meaning, and if nothing were owned, then how would it be possible to steal? To steal means to take someone else’s property without permission, and this is where the contradiction comes in. It is not possible to steal if nothing belongs to anyone. Thus, it is not possible to universalize this maxim, and we thereby get the duty that we should not steal. Both of these contradictions are what Kant calls “contradictions in conception.”

Another example Kant gives is of our obligation to help out others. Suppose you could help people but did not want to. Your maxim might be, “I will never help out anyone else since everyone should be independent.” If this were universalized, then everyone would be completely independent, with no one asking for nor offering help. However, we would not be able to live in a world where no one helps anyone because we will inevitably sometimes need others’ help. The contradiction in this case is a practical contradiction, “a contradiction in will,” as Kant calls it. In this case, we would eventually have to break the maxim due to our need for help. Thus, from this, we get the duty that we should sometimes help out others in need.

Problems With the First Formulation

One criticism that Kant faced among his contemporaries was for his stance on lying, since he said that we always have a duty to be truthful to others (Metaphysics of Morals 8:426). His reasoning seems to be that if we were to try to universalize a maxim that permits lying, such as “I will lie whenever it’s convenient to get what I want,” then people would be lying constantly, and it would lead to the concepts of “lie” and “truth” becoming meaningless. Thus, since “lie” would no longer mean anything, it is impossible to universalize this maxim, and thus, we should never lie. His contemporaries thought there must be cases where lying is permissible, and Kant responded in his essay “On a Supposed Right to Lie From Philanthropy.” In this essay, Kant imagined a situation that would seem to permit lying. Suppose that your friend is being pursued by someone who intends to kill him. Your friend comes to your house and asks to hide. You let him do so, and soon after, the killer is knocking at your door asking, “Is your friend inside?” Should you lie or not?

Kant asserts that you should not lie, even in these circumstances. Suppose your friend hears the killer knocking at the door and decides to flee out the back without your knowing. You lie and tell the killer that your friend is not here, and the killer leaves. Because of this, your friend and the killer bump into each other, and your friend is killed. Since your lie led them to bump into each other, you bear some responsibility for your friend’s death.

His general point is that consequences are uncertain. Importantly, Kant believes that consequences do not affect whether an action is right or wrong, and this example highlights why: because consequences are unpredictable. The type of rational approach to ethics that Kant prefers downplays the importance of consequences due to this unpredictability.

Another problem for the first formulation is that it is possible to imagine maxims that cannot be universalized but that do not seem to be immoral. For example, a stamp collector might live by the maxim, “I will buy but not sell stamps in order to expand my collection.” If everyone were to follow this, then the collector would not be able to buy because no one would be selling. This seems to lead to the implausible conclusion that collecting stamps (or collecting anything) is immoral.

Since Kant says that we are to “act only in accordance” with maxims that can be universalized, then any maxim that cannot be universalized is impermissible.

Some who want to defend Kant think that the problem is with how this maxim is phrased. The maxim specifies two actions: buying and not selling. If we split it into two maxims — “I will buy stamps to expand my collection” and “I will not sell stamps to expand my collection” — the problem can be avoided. This does point to a general difficulty with the first formulation, generally referred to as the “problem of relevant descriptions,” which is that there is often more than one way to describe the maxim underlying an action. And when we formulate it some ways (like in this case with the stamp collecting) it leads to a contradiction, whereas formulating it other ways does not.

Good Will

For Kant, just doing the right thing is not sufficient for making an action have full moral worth. It is also necessary to act with good will, by which Kant means something like the inclination to do good or what is also known as a good character. He believes that a good will is essential for morality. This is intuitively plausible because it seems that if an otherwise good action is done with bad or selfish intentions, that can rob the action of its moral goodness. If we imagine a man who goes to work at a soup kitchen to help out the poor, that seems like a good action. But if he is going there just to impress someone who works there, then that is less virtuous. And if he is going there to embezzle money from the charity, the action would be morally wrong.

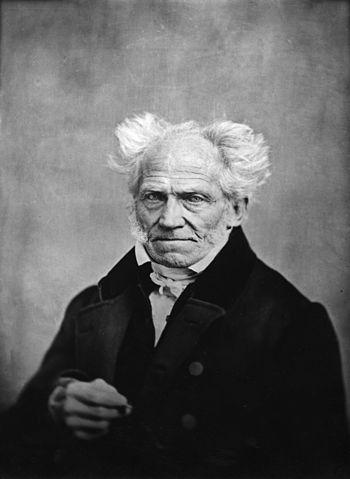

Less intuitive is that Kant thinks the only possible genuine good will is respect for the moral law. Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) would later describe Kant’s position as :

a deed must be performed simply and solely out of regard for the known law and for the concept of duty…. It must not be performed from any inclination, any benevolence felt towards others, any tender-hearted sympathy, compassion, or emotion of the heart.” ([1818] 1969, 526)

That is, when you do something because it is the right thing to do, that alone counts as good will.

Schopenhauer was a critic of Kant’s philosophy, including his ethics, and he objected that Kant’s view of the good will is “directly opposed to the genuine spirit of virtue; not the deed, but the willingness to do it, the love from which it results, and without which it is a dead work, this constitutes its meritorious element” ([1818] 1969, 526). Schopenhauer thought that good people are good because they want to do good actions and feel love and compassion towards others. If we return to the example of working in the soup kitchen, if the person is showing up to the soup kitchen because he likes helping people or feels compassion for the people he helps and wants to improve their lot, Schopenhauer would say this is a good person and, thus, a virtuous action.

Kant defended his position on good will by saying that an action done out of love or compassion is not fully autonomous. Autonomy means self-rule, and Kant saw it as a necessary condition for freedom and morality. If an action is not done autonomously, it is not really morally good or bad. Again, if our friend at the soup kitchen is working there because of some implant in his brain by which another person is able to control his every action, then the action is neither autonomous nor morally commendable.

Concerning acting out of love and compassion, Kant believed that when people act due to their emotions, then their emotions are in control not their rationality. To be truly autonomous, for Kant, an action must be done because of reason. An action done because of emotion is not fully free and not quite fully moral. This does not mean you should not enjoy doing good things. It just means that this should not be the reason underlying the action. According to Kant’s ethics, it is morally commendable for a person, acting out of good will, to decide that helping at the soup kitchen is the right thing to do, to go there, and then to thoroughly enjoy doing so and feel great compassion for the people helped. The important point is that reason you do an action should be because you have determined that it is the right thing to do.

Figure 15.1: “Arthur Schopenhauer by J Schäfer, 1859b” by Johann Schäfer (1859), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

The Second Formulation of the Categorical Imperative

The idea underlying the second formulation is that all humans are intrinsically valuable. As Kant writes, “What has a price can be replaced by something else as its equivalent; what on the other hand is raised above all price and therefore admits of no equivalent has a dignity” (Groundwork 4.434). What has a price is a thing, but a person has dignity and is, thus, beyond price and irreplaceable. It follows that a person with dignity deserves respect and should not be treated as a thing.

Kant expresses this idea in the second formulation of his categorical imperative: “So act that you use humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, always at the same time as an end, never merely as a means” (Groundwork 4:429).

That is, we should not treat people merely as means to ends; we should treat them as ends, including ourselves. To treat someone merely as a means does not give the person the proper respect — to fail to treat the person with dignity and, instead, treat them as a thing. It makes sense to use inanimate objects as tools — you can use a hammer as a means to drive in nails without worrying about how the hammer feels about this because it is a thing. But if you use a person in such a way, it devalues the person. Similarly, if you harm, take advantage of, or steal from someone, then you treat that person as a thing, as a means to your ends. Conversely, if you treat someone with respect, dignity, and as having unlimited value, then you treat the person as an end.

One important thing to add is that Kant says we should never treat people “merely as a means.” The “merely” is there to acknowledge that we can treat people as means, so long as we do not only treat them as means. It is not unusual to have to use other people for their skills or knowledge, so it is necessary to sometimes treat people as means. For example, imagine that your pipes need fixing, and you call a plumber. You are using the plumber as a means because he is making your end (to fix your pipes) his end, but there is nothing wrong with this if you also treat him as an end — that is, if you are respectful and pay him appropriately. The plumber’s end is to make a living with his plumbing skills. By paying him the agreed-upon amount, you are making his end (earning a living) your end. Thus, in this situation, you both are effectively advancing each others’ ends at the same time and, thus, treating each other both as ends and means.

One way to think of the idea of treating someone as ends and means is that, when you treat people as ends, you make their ends your ends, and when you treat people as means, you force them to make their ends your ends. To explain, let us look at an example from the first formulation. Since the first formulation and the second formulation of the categorical imperative are supposed to be saying the same thing, they should come to exactly the same conclusions about what is right and wrong. Thus, since we discovered earlier that it is wrong to make a false promise, then the second formulation should also tell us that false promises are wrong.

In our example, you made the false promise because you needed to borrow money to pay off debts; thus, your end was to pay off debts, and by lying to your friend, you are forcing him to make your end (paying off debts) his end. If you told your friend that you needed money and might not be able to pay it back, your friend would be able to decide. He might decide to make your end his end (to pay off your debts for you), but by depriving him of that choice, you are treating him as an object. For similar reasons, we can also conclude that any time we deceive someone, we are treating the person as a mere means to our ends.

We can also look at the other example from the first formulation discussed above and see that it leads to the same conclusion. Kant argued that we have an obligation to sometimes help out others in need. To help people out is to make their ends our ends. For example, if you see that someone is poor and hungry, his end at that point might be to get food. If you give him food or money to buy food, you are making it your end to feed him. Since you should treat people as ends, then that means you should sometimes provide people with help.

In addition, the second formulation also includes the idea that we should not treat ourselves as a mere means to ends. In the Groundwork, Kant gives two examples of duties to oneself:

- We should not commit suicide.

- We should cultivate some of our useful talents.

In the Metaphysics of Morals, Kant presents several more, including that you should not pursue greedy avarice, stupefy yourself with excessive food or drink, nor be excessively servile.

On the Morality of Suicide

The question of the morality of suicide was a heated topic of debate in the Western intellectual tradition in Kant’s day. Though we nowadays tend to think of suicide as a mental health issue and, thus, as a medical concern, it used to be much more often considered a moral concern. Suicide was a punishable crime in England until 1961, and both attempted and successful suicide could lead to serious penalties, with similar laws in many other countries.

The immorality of suicide was espoused by several influential Christian thinkers:

- Augustine, in his City of God (Book I, ch. 20), declared that the commandment, “Thou shalt not kill,” included suicide.

- Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Theologiae (II-II, Q. 64, A. 5), argued that (1) since our natural inclination is to try to stay alive and extend our life as long as possible, suicide is unnatural and therefore wrong, that (2) since our community benefits from our continued existence, then suicide harms the community, and that (3) since our life is not our own, being a gift from God, then committing suicide is a crime against God. Thus, suicide harms the self, society, and God.

- Dante, in his Inferno (Canto XIII), placed those who had committed suicide in the Second Ring of the Seventh Circle of Hell, for those who commit violence against the self ([1320] 1995).

Such arguments were influential in Kant’s day. His own arguments in the Groundwork are that (1) since suicide is motivated by self-interestedness (by a desire to end the sorrows a person is experiencing) and since self-interestedness normally impels us to try to improve our life, then suicide is self-contradictory and thus wrong (4:422) and that (2) by committing suicide one is treating oneself merely as a means and not as an end (4:429). Also, in his Metaphysics of Morals, he argues that suicide effectively harms the morality in the world by destroying one’s capacity for morality within oneself (6:423).

There were other authors who disagreed:

- Much earlier, in Utopia, Thomas More argued that suicide should be permitted in cases when people suffer from unpleasant and incurable diseases ([1516] 2012).

- Arthur Schopenhauer took the view in On Suicide that suicide, though not a sensible choice in most cases, cannot be considered morally wrong because your life and person are the things that most clearly belong to you ([1851] 2015). Thus, you can dispose of them how you wish.