Chapter 8: Why Be Moral?

Jessica’s note (Open Press) – Mon Oct 27, 2025: Just a quick note, this chapter includes links that look like footnotes (for example, [1]), but they’re actually hyperlinks formatted to look like footnotes.

Introduction

This debate is about justice and injustice, and it explores Plato’s ideas on what it means to be just. The reading suggests that people often act justly not because they truly value justice, but because they’re afraid of the consequences of being unjust or causing harm to others.

Glaucon’s speech is important—he questions whether people naturally lean toward injustice if they can get away with it. He wonders if being unjust might be more appealing than being just. Adeimantus also challenges Socrates, especially on the idea that virtue (or moral goodness) is valuable all by itself, even without rewards. Meanwhile, Glaucon is open to Socrates’s argument and wants to explore whether justice really is better than injustice.

– KELLY STANLEY

Reading 1: Plato — “The Ring of Gyges”

Republic

Book II

SOCRATES – GLAUCON

WITH these words I was thinking that I had made an end of the discussion; but the end, in truth, proved to be only a beginning. For Glaucon, who is always the most pugnacious of men, was dissatisfied at Thrasymachus’ retirement; he wanted to have the battle out. So he said to me: Socrates, do you wish really to persuade us, or only to seem to have persuaded us, that to be just is always better than to be unjust?

I should wish really to persuade you, I replied, if I could.

Then you certainly have not succeeded. Let me ask you now:–How would you arrange goods–are there not some which we welcome for their own sakes, and independently of their consequences, as, for example, harmless pleasures and enjoyments, which delight us at the time, although nothing follows from them?

I agree in thinking that there is such a class, I replied.

Is there not also a second class of goods, such as knowledge, sight, health, which are desirable not only in themselves, but also for their results?

Certainly, I said.

And would you not recognize a third class, such as gymnastic, and the care of the sick, and the physician’s art; also the various ways of money-making–these do us good but we regard them as disagreeable; and no one would choose them for their own sakes, but only for the sake of some reward or result which flows from them?

There is, I said, this third class also. But why do you ask?

Because I want to know in which of the three classes you would place justice?

In the highest class, I replied,–among those goods which he who would be happy desires both for their own sake and for the sake of their results.

Then the many are of another mind; they think that justice is to be reckoned in the troublesome class, among goods which are to be pursued for the sake of rewards and of reputation, but in themselves are disagreeable and rather to be avoided.

I know, I said, that this is their manner of thinking, and that this was the thesis which Thrasymachus was maintaining just now, when he censured justice and praised injustice. But I am too stupid to be convinced by him.

I wish, he said, that you would hear me as well as him, and then I shall see whether you and I agree. For Thrasymachus seems to me, like a snake, to have been charmed by your voice sooner than he ought to have been; but to my mind the nature of justice and injustice have not yet been made clear. Setting aside their rewards and results, I want to know what they are in themselves, and how they inwardly work in the soul. If you, please, then, I will revive the argument of Thrasymachus. And first I will speak of the nature and origin of justice according to the common view of them. Secondly, I will show that all men who practise justice do so against their will, of necessity, but not as a good. And thirdly, I will argue that there is reason in this view, for the life of the unjust is after all better far than the life of the just–if what they say is true, Socrates, since I myself am not of their opinion. But still I acknowledge that I am perplexed when I hear the voices of Thrasymachus and myriads of others dinning in my ears; and, on the other hand, I have never yet heard the superiority of justice to injustice maintained by any one in a satisfactory way. I want to hear justice praised in respect of itself; then I shall be satisfied, and you are the person from whom I think that I am most likely to hear this; and therefore I will praise the unjust life to the utmost of my power, and my manner of speaking will indicate the manner in which I desire to hear you too praising justice and censuring injustice. Will you say whether you approve of my proposal?

Indeed I do; nor can I imagine any theme about which a man of sense would oftener wish to converse.

I am delighted, he replied, to hear you say so, and shall begin by speaking, as I proposed, of the nature and origin of justice.

GLAUCON

They say that to do injustice is, by nature, good; to suffer injustice, evil; but that the evil is greater than the good. And so when men have both done and suffered injustice and have had experience of both, not being able to avoid the one and obtain the other, they think that they had better agree among themselves to have neither; hence there arise laws and mutual covenants; and that which is ordained by law is termed by them lawful and just. This they affirm to be the origin and nature of justice;–it is a mean or compromise, between the best of all, which is to do injustice and not be punished, and the worst of all, which is to suffer injustice without the power of retaliation; and justice, being at a middle point between the two, is tolerated not as a good, but as the lesser evil, and honoured by reason of the inability of men to do injustice with impunity. For no man who is worthy to be called a man would ever submit to such an agreement if he were able to resist; he would be mad if he did. Such is the received account, Socrates, of the nature and origin of justice.

Now, that those who practise justice do so involuntarily and because they have not the power to be unjust will best appear if we imagine something of this kind: having given both to the just and the unjust power to do what they will, let us watch and see whither desire will lead them; then we shall discover in the very act the just and unjust man to be proceeding along the same road, following their interest, which all natures deem to be their good, and are only diverted into the path of justice by the force of law. The liberty which we are supposing may be most completely given to them in the form of such a power as is said to have been possessed by Gyges the ancestor of Croesus the Lydian. According to the tradition, Gyges was a shepherd in the service of the king of Lydia; there was a great storm, and an earthquake made an opening in the earth at the place where he was feeding his flock. Amazed at the sight, he descended into the opening, where, among other marvels, he beheld a hollow brazen horse, having doors, at which he, stooping and looking in, saw a dead body of stature, as appeared to him, more than human, and having nothing on but a gold ring; this he took from the finger of the dead and reascended. Now the shepherds met together, according to custom, that they might send their monthly report about the flocks to the king; into their assembly he came having the ring on his finger, and, as he was sitting among them, he chanced to turn the collet of the ring inside his hand, when instantly he became invisible to the rest of the company and they began to speak of him as if he were no longer present. He was astonished at this, and again touching the ring he turned the collet outwards and reappeared; he made several trials of the ring, and always with the same result: when he turned the collet inwards, he became invisible; when outwards, he reappeared. Whereupon he contrived to be chosen one of the messengers who were sent to the court; where as soon as he arrived he seduced the queen, and with her help conspired against the king and slew him, and took the kingdom.

Suppose now that there were two such magic rings, and the just put on one of them and the unjust the other; no man can be imagined to be of such an iron nature that he would stand fast in justice. No man would keep his hands off what was not his own when he could safely take what he liked out of the market, or go into houses and lie with any one at his pleasure, or kill or release from prison whom he would, and in all respects be like a god among men. Then the actions of the just would be as the actions of the unjust; they would both come at last to the same point. And this we may truly affirm to be a great proof that a man is just, not willingly or because he thinks that justice is any good to him individually, but of necessity, for, wherever any one thinks that he can safely be unjust, there he is unjust. For all men believe in their hearts that injustice is far more profitable to the individual than justice, and he who argues as I have been supposing, will say that they are right. If you could imagine any one obtaining this power of becoming invisible, and never doing any wrong or touching what was another’s, he would be thought by the lookers-on to be a most wretched idiot, although they would praise him to one another’s faces and keep up appearances with one another from a fear that they too might suffer injustice. Enough of this.

Now, if we are to form a real judgement of the life of the just and unjust, we must isolate them; there is no other way; and how is the isolation to be effected? I answer: let the unjust man be entirely unjust, and the just man entirely just; nothing is to be taken away from either of them, and both are to be perfectly furnished for the work of their respective lives. First, let the unjust be like other distinguished masters of craft; like the skilful captain or physician, who knows intuitively his own powers and keeps within their limits, and who, if he fails at any point, is able to recover himself. So let the unjust make his unjust attempts in the right way, and lie hidden if he means to be great in his injustice (he who is found out is nobody): for the highest reach of injustice is: to be deemed just when you are not. Therefore, I say that, in the perfectly unjust man, we must assume the most perfect injustice; there is to be no deduction, but we must allow him, while doing the most unjust acts, to have acquired the greatest reputation for justice. If he has taken a false step, he must be able to recover himself; he must be one who can speak with effect if any of his deeds come to light; and, where force is required, he must have the aid of courage, strength and the abundance of money and friends that he has accumulated.

And, at his side, let us place the just man in his nobleness and simplicity, wishing, as Aeschylus says, to be and not to seem good. There must be no seeming, for, if he seems to be just, he will be honoured and rewarded, and then we shall not know whether he is just for the sake of justice or for the sake of honours and rewards; therefore, let him be clothed in justice only, and have no other covering; and he must be imagined in a state of life the opposite of the former. Let him be the best of men, and let him be thought the worst; then he will have been put to the proof; and we shall see whether he will be affected by the fear of infamy and its consequences. And let him continue thus to the hour of death; being just and seeming to be unjust. When both have reached the uttermost extreme, the one of justice and the other of injustice, let judgement be given which of them is the happier of the two.

SOCRATES – GLAUCON

Heavens! My dear Glaucon, I said, how energetically you polish them up for the decision, first one and then the other, as if they were two statues.

I do my best, he said. And, now that we know what they are like, there is no difficulty in tracing out the sort of life that awaits either of them. This I will proceed to describe, but, as you may think the description a little too coarse, I ask you to suppose, Socrates, that the words which follow are not mine; let me put them instead into the mouths of the eulogists of injustice: they will tell you that the just man who is thought unjust will be scourged, racked, bound; will have his eyes burnt out; and, at last, after suffering every kind of evil, he will be impaled; then he will understand that he ought to seem only, and not to be, just. The words of Aeschylus may be more truly spoken of the unjust than of the just, for the unjust is pursuing a reality; he does not live with a view to appearances; he wants to be really unjust and not merely to seem so:

His mind has a soil deep and fertile,

Out of which spring his prudent counsels.[Septem 592 sq]

In the first place, he is thought just and therefore bears rule in the city. He can marry whom he will and give in marriage to whom he will; also, he can trade and deal where he likes and always to his own advantage, because he has no misgivings about injustice; and, at every contest, whether in public or in private, he gets the better of his antagonists and gains at their expense, and is rich; and, out of his gains, he can benefit his friends and harm his enemies; moreover, he can offer sacrifices and dedicate gifts to the gods abundantly and magnificently, and can honour the gods or any man whom he wants to honour in a style far better than the just and, therefore, is likely to be dearer than they are to the gods. And thus, Socrates, gods and men are said to unite in making the life of the unjust better than the life of the just. . . .

This is an abridged version of The Ring of Gyges by Plato, edited by Douglas Giles. The original work is in the public domain and available via Pressbooks: https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/classicreadings/chapter/plato-on-justice/. Abridgment and adaptation by Grace Boehm, 2025.

Unless otherwise noted, “Plato – On Justice” by Plato (2017) in The Originals: Classic Readings in Western Philosophy [edited by Jeff McLaughlin] is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Contemporary Language Edition

Reading 2: Sarah Hrdy — “Apes on a Plane”

Used with permission. Not subject to the Creative Commons license of this publication.

However selfish . . . man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature which interest him in the fortunes of others.

—Adam Smith (1759)

Each year 1.6 billion passengers fly to destinations around the world. Patiently we line up to be checked and patted down by someone we’ve never seen before. We file on board an aluminum cylinder and cram our bodies into narrow seats, elbow to elbow, accommodating one another for as long as the flight takes.

With nods and resigned smiles, passengers make eye contact and then yield to latecomers pushing past. When a young man wearing a backpack hits me with it as he reaches up to cram his excess paraphernalia into an overhead compartment, instead of grimacing or baring my teeth, I smile (weakly), disguising my irritation. Most people on board ignore the crying baby, or pretend to. A few of us are even inclined to signal the mother with a sideways nod and a wry smile that says, “I know how you must feel.” We want her to know that we understand, and that the disturbance she thinks her baby is causing is not nearly as annoying as she imagines, even though we also can intuit, and so can she, that the young man beside her, who avoids looking at her and keeps his eyes determinedly glued to the screen of his laptop, does indeed mind every bit as much as she fears.

Thus does every frequent flier employ on a regular basis peculiarly empathic aptitudes for theorizing about the mental states and intentions of other people, our species’ gift for mutual understanding. Cognitively oriented psychologists refer to the ability to think about what someone else knows as having a “theory of mind.”[1] They design clever experiments to determine at what age human children acquire this ability and to learn how good at mind reading (or more precisely, attributing mental states to others) nonhuman animals are. Other psychologists prefer the related term “intersubjectivity,” which emphasizes the capacity and eagerness to share in the emotional states and experiences of other individuals—and which, in humans at least, emerges at a very early stage of development, providing the foundation for more sophisticated mind reading later on.[2]

Whatever we call it, this heightened interest in and ability to scan faces, and our perpetual quest to understand what others are thinking and intending, to empathize and care about their experiences and goals, help make humans much more adept at cooperating with the people around us than other apes are. Far oftener than any of us are aware, humans intuit the mental experiences of other people, and—the really interesting thing—care about having other people share theirs. Imagine two seat-mates on this plane, one of whom develops a severe migraine in the course of the flight. Even though they don’t speak the same language, her new companion helps her, perhaps holding a wet cloth to her head, while the sick woman tries to reassure her that she is feeling better. Humans are often eager to understand others, to be understood, and to cooperate. Passengers crowded together on an aircraft are just one example of how empathy and intersubjectivity are routinely brought to play in human interactions. It happens so often that we take the resulting accommodations for granted. But just imagine if, instead of humans being crammed and annoyed aboard this airplane, it were some other species of ape.

At moments like this, it is probably just as well that mind reading in humans remains an imperfect art, given the oddity of my sociobiological musings. I cannot keep from wondering what would happen if my fellow human passengers suddenly morphed into another species of ape. What if I were traveling with a planeload of chimpanzees? Any one of us would be lucky to disembark with all ten fingers and toes still attached, with the baby still breathing and unmaimed. Bloody earlobes and other appendages would litter the aisles. Compressing so many highly impulsive strangers into a tight space would be a recipe for mayhem.

Once acquired, the habit of comparing humans with other primates is hard to shake. My mind flits back to one of the earliest accounts of the behavior of Hanuman langurs, a type of Asian monkey that, as a young woman, I went to India to study. T. H. Hughes was a British functionary and amateur naturalist who had been sent out to the subcontinent to help govern the Raj. “In April 1882, when encamped at the village of Singpur in the Sohagpur district of Rewa state . . . My attention was attracted to a restless gathering of ‘Hanumans,’” wrote Hughes. As he watched, a fight broke out between two males, one of them traveling with a group of females, the other presumably a stranger. “I saw their arms and teeth going viciously, and then the throat of one of the aggressors was ripped right open and he lay dying.” At that point Hughes surmised that “the tide of victory would have been in [the stranger’s favor] had the odds against him not been reinforced by the advance of two females . . . Each flung herself upon him, and though he fought his enemies gallantly, one of the females succeeded in seizing him in the most sacred portion of his person, depriving him of his most essential appendages.”[3]

Descriptions of missing digits, ripped ears, and the occasional castration are scattered throughout the field accounts of langur and red colobus monkeys, of Madagascar lemurs, and of our own close relatives among the Great Apes. Even among famously peaceful bonobos, a type of chimpanzee so rare and difficult to access in the wild that most observations come from zoos, veterinarians sometimes have to be called in following altercations to stitch back on a scrotum or penis. This is not to say that humans don’t display similar propensities toward jealousy, indignation, rage, xenophobia, or homicidal violence. But compared with our nearest ape relations, humans are more adept at forestalling outright mayhem. Our first impulse is usually to get along. We do not automatically attack a stranger, and face-to-face killings are a much harder sell for humans than for chimpanzees. With 1.6 billion airline passengers annually compressed and manhandled, no dismemberments have been reported yet. The goal of this book will be to explain the early origins of the mutual understanding, giving impulses, mind reading, and other hypersocial tendencies that make this possible.

“Wired” to Cooperate

From a tender age and without special training, modern humans identify with the plights of others and, without being asked, volunteer to help and share, even with strangers. In these respects, our line of apes is in a class by itself. Think back to the tsunami in Indonesia or to hurricane Katrina. Confronted with images of the victims, donor after donor offered the same reason for giving: Helping was the only thing that made them feel better. People had a gut-level response to seeing anguished faces and hearing moaning recitals of survivors who had lost family members—wrenching cues broadcast around the world. This ability to identify with others and vicariously experience their suffering is not simply learned: It is part of us. Neuroscientists using brain scans to monitor neural activity in people asked to watch someone else do something like eating an apple, or asked just to imagine someone else eating an apple, find that the areas of the brain responsible for distinguishing ourselves from others are activated, as are areas of the brain actually responsible for controlling the muscles relevant to apple-eating. Tests in which people are requested to imagine others in an emotional situation produce similar results.[4] It is a quirk of mind that serves humans well in all sorts of social circumstances, not just acts of compassion but also hospitality, gift-giving, and good manners—norms that no culture is without.

Reflexively altruistic impulses are consistent with findings by neuroscientists who use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to monitor brain activity among experimentally paired strangers engaged in a variant of a famous game known as the Prisoner’s Dilemma. In this situation, two players earn rewards either by cooperating or defecting. If neither player defects and both continue to cooperate over sequential games, both gain more than they would have without playing at all. But if one player opts out while his partner cooperates, the defector wins even more and his partner gets nothing. If both defect, they lose out entirely. Such experiments yield a remarkable result. Even when players are told by the experimenters that this is going to be a one-shot game, so that each player has only one chance to cooperate or defect, with no possibility of cooperating again to mutual advantage, 42 percent of randomly selected strangers nevertheless opt to behave cooperatively.[5]

Such generosity at first seems irrational, especially to economists who are accustomed to celebrating individualism and economic models that assume self-interested “rational actors,” or to a sociobiologist like me who has devoted much of her professional life researching competition between primate males for access to fertile females, between females in the same group for resources, and even between offspring in the same family for access to nourishment and care. When considered in the context of how humankind managed to survive vast stretches of time and dramatic fluctuations in climate during the Pleistocene, in the period from around 1.8 million years ago until about 12,000 BCE, such generous tendencies turn out to be “better than rational” because people had to rely so much on time-tested relationships with others.[6]

Among people living in small, widely dispersed bands of interconnected families likely to interact again and again, prosocial impulses—meaning tendencies to voluntarily do things that benefit others—are likely to be reciprocated or rewarded. The generous person’s well-being and that of his or her family depended more on maintaining the web of social relationships that sustained them through good times and bad than on the immediate outcome of a particular transaction. The people you treat generously this year, with the loan of a tool or gift of food, are the same people you depend on next year when your waterholes dry up or game in your home range disappears.[7] Over their lifetimes people would encounter and re-encounter their neighbors, not necessarily often, but again and again. Failures to reciprocate would result in loss of allies or, worse still, social exclusion.[8]

Jump ahead thousands of years to the laboratories where researchers administer such experiments today. As shown by research subjects who cooperate even when there is no possibility for the favor to be reciprocated, “one-shot deals” are not an eventuality that human brains were designed to register. Right from an early age, even before they can talk, people find that helping others is inherently rewarding, and they learn to be sensitive to who is helpful and who is not.[9] Regions of the brain activated by helping are the same as those activated when people process other pleasurable rewards.[10]

Anyone who assumes that babies are just little egotists who enter the world needing to be socialized so they can learn to care about others and become good citizens is overlooking other propensities every bit as species-typical. Humans are born predisposed to care how they relate to others. A growing body of research is persuading neuroscientists that Baruch Spinoza’s seventeenth-century proposal better captures the full range of tensions humans grow up with. “The endeavor to live in a shared, peaceful agreement with others is an extension of the endeavor to preserve oneself.” Emerging evidence is drawing psychologists and economists alike to conclude that “our brains are wired to cooperate with others” as well as to reward or punish others for mutual cooperation.[11]

Perhaps not surprisingly, helpful urges are activated most readily when people deal with each other face-to-face. Specialized regions of the human brain, huge areas of the frontal and parietotemporal cortex, are given over to interpreting other people’s vocalizations and facial expressions. Right from the first days of life, every healthy human being is avidly monitoring those nearby, learning to recognize, interpret, and even imitate their expressions. An innate capacity for empathizing with others becomes apparent within the first six months.[12] By early adulthood most of us will have become experts at reading other people’s intentions. So attuned are we to the inner thoughts and feelings of those around us that even professionals trained not to respond emotionally to the distress of others find it difficult not to be moved. Therapists face particular challenges in this respect. Empathy, the stock-in-trade of psychotherapists because it really does produce better results, turns out to be their worst nightmare as well.[13] People who deal day-in-and-day-out with the troubles of others face such occupational hazards as “vicarious traumatization” and “compassion fatigue,” or face the threat of “catching” a client’s depression.[14]

New discoveries by evolutionarily minded psychologists, economists, and neuroscientists are propelling the cooperative side of human nature to center stage. New findings about how irrational, how emotional, how caring, and even how selfless human decisions can be are transforming disciplines long grounded in the premise that the world is a competitive place where to be a rational actor means being a selfish one. Researchers from diverse fields are converging on the realization that while humans can indeed be very selfish, in terms of empathic responses to others and our eagerness to help and share with them, humans are also quite unusual, notably different from other apes.[15]

“Without prosocial emotions,” two theoretical economists opined recently, “we would all be sociopaths, and human society would not exist, however strong the institutions of contract, governmental law enforcement and reputation.”[16] Coming from practitioners of the dismal science, this is revolutionary stuff. For evolutionists, it requires either special pleading or else new ways of thinking about how our species evolved and what being human means.

What It Means to Be Emotionally Modern

Time and again, anthropologists have drawn lines in the sand dividing humans from other animals, only to see new discoveries blur the boundaries. We drew up these lists of uniquely human attributes without realizing how much more they revealed about our ignorance of other animals than about the special attributes of our species. By the middle of the twentieth century, Man the Toolmaker had lost pride of place as Japanese and British researchers watched wild chimpanzees tailor twigs to fish for termites.[17] By now, every one of the Great Apes is known to select, prepare, and use tools, crafting natural objects into sponges, umbrellas, nutcrackers—even sharpening sticks for jabbing prey.[18] Furthermore, Great Apes have unquestionably been using tools for a long time. Archaeologists trace the special stone mortars that chimpanzees in west Africa use for nut cracking back in time at least 4,300 years.[19]

Great Apes employ tools in a wide range of contexts, and do so spontaneously, inventively, and sometimes with apparent foresight. In a recent article in Science magazine titled “Apes Save Tools for Future Use,” Nicholas Mulcahy and Josep Call describe orangutan and bonobo subjects who were trained to use particular tools to solve a problem and earn a reward, and then were permitted to select particular tools to bring with them for tasks they would be asked to perform an hour later. They chose the tools likely to be most useful. Such experiments have led primatologists (and even comparative psychologists working with smart birds like corvids) to credit nonhuman animals with some ability to plan ahead.[20]

Arguably, Great Apes have been making and using tools since they last shared common ancestors with humans and with each other, and they transmitted this technological expertise along with various behaviors (like grooming protocol or greeting ceremonies) from one generation to another so that different populations have different repertories. Other apes also store memories much as we do, and in terms of spatial cognition or traits such as their ability to remember ordered symbols that briefly flash up on a computer screen, specially trained chimpanzees test better than graduate students.[21] In general, the basic cognitive machinery for dealing with their physical worlds is remarkably similar in humans and other apes.[22]

What about locomotion as the distinguishing trait? A key criterion of humanness, upright walking on two legs, bit the dust with the discovery of a fossilized trail of bipedal footprints left in volcano ash by australopithecines—apes with brains no bigger than a chimpanzee’s—some four million years ago. Fossilized footprints together with fossilized skeletal remains made it clear that these long-armed, small-brained, extraordinarily chimplike creatures were walking upright millions of years before the emergence of the genus Homo.[23]

Bipedality is not what makes us human, and as clever as we think we are, the really big differences between chimpanzees and humans do not lie in the realm of basic spatial cognition or memory.[24] Apart from language, where humankind’s uniqueness has never been in serious dispute, the last outstanding distinction between us and other apes involves a curious packet of hypersocial attributes that allow us to monitor the mental states and feelings of others, as scientists at the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology have recently suggested.

This institute is the premier place for studying psychological traits possessed by humans and other apes. Part of its ambitiously interdisciplinary research project is housed in a large building in the heart of the historic German city of Leipzig. Its offices and laboratories are filled with psychologists, behavioral ecologists, primatologists, and geneticists, who in a technical tour de force were recently able to extract DNA from extinct Neanderthals and compare it with that from modern humans. Research on children’s cognitive development goes on here as well. The other branch of the institute is located a short distance away, in a sprawling zoological garden that is home to social groups of gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and orangutans. Special laboratories enable scientists to conduct experiments on ape cognition, including recent experiments showing that bonobos and orangutans can plan ahead. All five species—human children and the four Great Apes—are being studied simultaneously using comparable methods, with spectacular results.

In 2005 Michael Tomasello, the American-born leader of the Max Planck team, proposed a new dividing line between humans and nonhuman apes. “We propose,” he and his colleagues announced, “that the crucial difference between human cognition and that of other species is the ability to participate with others in collaborative activities with shared goals and intentions.”[25] For the moment, this trait, along with our extralarge brains and capacity for language, marks the new dividing line separating our natures from those of other apes. Accordingly, “human beings, and only human beings, are biologically adapted for participating in collaborative activities involving shared goals and socially coordinated action plans.”[26] Only among humans do we find large-scale cooperative endeavors involving people who are not necessarily close kin. Only humans, for example, can fan out around an encampment, gather building materials, consciously register the mental blueprint someone else has in mind, and chip in to help construct a shelter.

Humans “are the world’s experts at mind reading,” far more “biologically adapted” to collaborate with others than any other ape, Tomasello stresses. To him, these aptitudes are nearly synonymous with our special ability to perceive what others know, intend, and desire.[27] Human infants are not just social creatures, as other primates are; they are “ultrasocial.”[28] Unlike chimpanzees and other apes, almost all humans are naturally eager to collaborate with others. They may prefer engaging with familiar kin, but they also easily coordinate with nonkin, even strangers. Given opportunities, humans develop these proclivities into complex enterprises, such as collaboratively tracking and hunting prey, processing food, playing cooperative games, building shelters, or designing spacecraft that reach the moon.[29]

At some point in the course of their evolution, our ancestors became more deeply interested in monitoring the intentions of others and eager to share their inner feelings and thoughts as well as their mental states. This interest laid the groundwork for the peculiarly cooperative natures that would distinguish these hominins from other bipedal apes and rendered apes in the line leading to the genus Homo what I think of as emotionally modern.[30] My goal in writing this book is to understand how such other-regarding tendencies could have evolved in creatures as self-serving as apes are.

The fact that humans are better equipped to cooperate than other apes does not mean that men do not compete with one another for status or for access to mates, or that women are not also fiercely competitive in the domains that matter to them, striving for desirable mates, local clout, and access to resources for themselves and their children. Such status quests are primate-wide propensities, and, under pressure, conflict boils over into violence. Nevertheless, as Tomasello emphasizes, people’s peculiar eagerness to read and share the feelings and concerns of others, their quest for intersubjective engagement and mutual understanding, provides the underpinning for behaving in a more prosocial way. It is what makes humans so much more desirable as travel companions than other apes are. So where did this human questing for intersubjective engagement come from?

To Care and to Share is to Survive

The benefits to humans of their other-regarding tendencies have never been in doubt. This mutual understanding provided the foundation for the evolution of cooperative behaviors. Before returning to the perplexing question about origins so central to this book, namely, “How on Darwin’s earth did the stage for such cooperation get set?” I briefly want to remind readers why (once the initial propensities had evolved) being eager to share and willing to cooperate were so critical during the long stretch of time when our ancestors lived as hunters and gatherers. That done, we can return to the question of origins, and ask how mind reading, empathy, and the other underpinnings for higher levels of cooperation became so well developed in one particular line of apes. Still later developments, having to do with the evolution of our unique intelligence, language, and other critical components of human-level cooperation, are beyond the scope of this book. So let’s start with sharing, a quintessentially human trait.

During the voyage of the Beagle when the young Charles Darwin first encountered the “savages” living in Tierra del Fuego, he was amazed to realize that “some of the Fuegians plainly showed that they had a fair notion of barter . . . I gave one man a large nail (a most valuable present) without making any signs for a return; but he immediately picked out two fish, and handed them up on the point of his spear.”[31] Why would sharing with others, even strangers, be so automatic? And why, in culture after culture, do people everywhere devise elaborate customs for the public presentation, consumption, and exchange of goods?

Gift exchange cycles like the famous “kula ring” of Melanesia, where participants travel hundreds of miles by canoe to circulate valuables, extend across the Pacific region and can be found in New Zealand, Samoa, and the Trobriand Islands. In New Caledonia, giant yams are publicly displayed in the Pilu Pilu ceremonies, while among the Kwakiutl, Haida, or Tsimshian peoples along the resource-rich coast of northwest North America as well as among the Koryak or Chuckchee peoples of Siberia, quantities of possessions are publicly shared and destroyed in elaborate potlatch ceremonies. As I write these words, I am reminding myself to update the long lists of recipients to whom we send cards and boxes of fresh walnuts each Christmas—my own tribe’s custom for staying in touch with distant kin and as-if kin, the creation of which is a specialty of the human species. The point is not merely to share but to establish and maintain social networks, as Marcel Mauss argued in one of anthropology’s early classics, Essai sur le don (The Gift). This is why dopamine-related neural pleasure centers in human brains are stimulated when someone acts generously or responds to a generous act.[32]

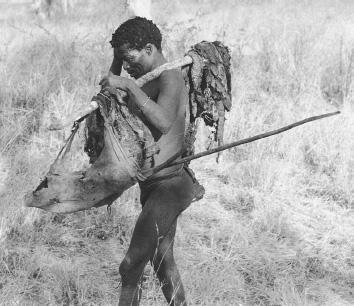

One of the earliest in-depth studies of traditional exchange networks was undertaken by the anthropologist Polly Wiessner, who has done extensive fieldwork in Africa and New Guinea. She began her Kalahari research in the 1970s among the San-speaking Ju/’hoansi people, also known as the !Kung or Bushmen, who at that time still lived as mobile gatherers and hunters belonging to one of the most venerable human groups on earth. Genetic comparisons of mitochondrial DNA across extant human populations indicate that ancestors of this relatively isolated population of Khoisan people, along with those of some other remnant foragers in Central Africa, split off from humankind’s founding population at a very early date. Both men and women carry the mitochondrial DNA characteristic of the deepest roots of the African phylogenetic tree from which all modern humans descend.[33]

As among our earliest Pleistocene ancestors, Ju/’hoansi women gathered and the men hunted, with communities sharing the fruits of their labors. Over the next thirty years, Wiessner followed the lives of group members even after they were displaced from their traditional foraging grounds. Today, their descendants eke out a living by gardening and herding when they can, subsisting on government handouts or “lying out the hunger”—patiently suffering—when they can’t. When they still roamed across the semi-arid Kalahari, with no way to store food, these people understood that their most important resources were their reputations and the stored goodwill of others.

The sporadic success and frequent failures of big-game hunters is a chronic challenge for hungry families among traditional hunter-gatherers. One particularly detailed case study of South American foragers suggests that roughly 27 percent of the time a family would fall short of the 1,000 calories of food per person per day needed to maintain body weight. With sharing, however, a person can take advantage of someone else’s good fortune to tide him through lean times. Without it, perpetually hungry people would fall below the minimum number of calories they needed. The researchers calculated that once every 17 years, caloric deficits for nonsharers would fall below 50 percent of what was needed 21 days in a row, a recipe for starvation. By pooling their risk, the proportion of days people suffered from such caloric shortfalls fell from 27 percent to only 3 percent.[34]

For those who store social obligations rather than food, unspoken contracts—beginning with the most fundamental one between the group’s gatherers and its hunters, and extending to kin and as-if kin in other groups—tide them over from shortfall to shortfall. Time-honored relationships enable people to forage over wider areas and to reconnect with trusted exchange partners without fear of being killed by local inhabitants who have the advantage of being more familiar with the terrain.[35] When a waterhole dries up in one place, when the game moves away, or, perhaps most dreaded of all, when a conflict erupts and the group must split up, people can cash in on old debts and generous reputations built up over time through participation in well-greased networks of exchange.

The particular exchange networks that Wiessner studied among the Ju/’hoansi are called hxaro. Some 69 percent of the items every Bushman used—knives, arrows, and other utensils; beads and clothes—were transitory possessions, fleetingly treasured before being passed on in a chronically circulating traffic of objects. A gift received one year was passed on the next.[36] In contrast to our own society where regifting is regarded as gauche, among the Ju/’hoansi it was not passing things on—valuing an object more than a relationship, or hoarding a treasure—that was socially unacceptable. As Wiessner put it, “The circulation of gifts in the Kalahari gives partners information that they ‘hold each other in their hearts’ and can be called on in times of need.”[37] A distinctive feature of human social relations was this “release from proximity.” It meant that even people who had moved far away and been out of contact for many years could meet as fondly remembered friends years later.[38] Anticipation of goodwill helps explain the 2008 finding by psychologists at the University of British Columbia and Harvard Business School that spending money on other people had a more positive impact on the happiness of their study subjects than spending the same amount of money on themselves.[39]

In her detailed study of nearly a thousand hxaro partnerships over thirty years, Wiessner learned that the typical adult had anywhere from 2 to 42 exchange relationships, with an average of 16. Like any prudently diversified stock portfolio, partnerships were balanced so as to include individuals of both sexes and all ages, people skilled in different domains and distributed across space. Approximately 18 percent resided in the partner’s own camp, 24 percent in nearby camps, 21 percent in a camp at least 16 kilometers away, and 33 percent in more distant camps, between 51 and 200 kilometers away.[40]

Just under half of the partnerships were maintained with people as closely related as first cousins, but almost as many were with more distant kin.[41] Partnerships could be acquired at birth, when parents named a new baby after a future gift-giver (much as Christians designate godparents), or they could be passed on as a heritable legacy when one of the partners died. Since meat of large animals was always shared, people often sought to be connected with skilled hunters. This is why the best hunters tended to have very far-flung assortments of hxaro contacts, as did their wives.

Contacts were built up over the course of a life well-lived by individuals perpetually alert to new opportunities. When a parent died, his or her children or stepchildren inherited the deceased person’s exchange partners as well as kinship networks, and gifts were often given at that time to reinforce the continuity, since to give, share, and reciprocate was to survive.[42] Multiple systems for identifying kin linked people in different ways, increasing the number of people to whom an individual was related. One kinship system was based on marriage and blood ties, while another involved the name one was given, which automatically forged a tie to others with the same name. These manufactured or fictive kin were also referred to as mother, father, brother, or sister.

Such dual systems function to spread the web of kinship widely, and since the second system can be revised over the course of an individual’s lifetime, it becomes feasible for a namesake to bring even distant kin into a closer relationship when useful.[43] Every human society depends on some system of exchange and mutual aid, but foragers have elevated exchange to a core value and an elaborate art form. People construct vast and intricate terminologies to identify kin and as-if kin, in order to expand the potential for relationships based on trust. Depending on the situation, these can be activated and kept going by reciprocal exchange or left dormant until needed.

Marriages that Ju/’hoansi partners arranged for their children provided new opportunities to cast the net wider still. At marriage, band members offer gifts to the newlyweds that are then recycled among in-laws. A wife taken by force would be far less valuable than the same woman freely given by in-laws properly compensated and ready to reciprocate. Under conditions of high child mortality, a kinless woman would make a less advantageous mate than one whose family support system was intact, because children without maternal grandmothers and other kin to help nurture them would be less likely to survive. Kinship ties, together with the terminologies and relationships based on the exchange of goods and services that are used to reify them, increase the number of people that one could call upon, share with, count on to reciprocate, go to live with when in need, and elicit help from in rearing one’s young.[44] The advantage of casting the net of kinship as widely as possible is presumably why foraging people are far more likely to trace relatedness through both mother and father, as opposed to only one or the other line, as is more typical in the matrilineal or patrilineal descent systems that prevail in nonforaging societies.[45]

Archaeological evidence suggests that unilineal—and perhaps especially patrilineal—inheritance systems began to emerge when foragers in habitats rich with marine resources began living more sedentary lives at higher population densities, as they did in coastal South Africa from at least 4,300 years ago. As with most primates, population densities of Paleolithic foragers would have varied across their range, from very low (with less than one person per square mile) to somewhat higher.[46]

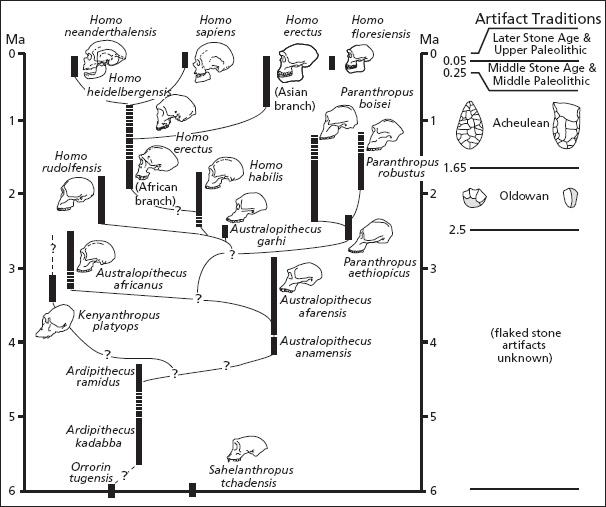

Consider one of the most successful, widespread, and long-lived of all hominins, Homo erectus, which first emerged around 1.8 million years ago. Some members of this highly variable (or polytypic) species must have migrated out of Africa early on. Fossils from an archaic form of Homo erectus are being unearthed at the Dmanisi site in the Republic of Georgia, with other remnants uncovered in Java, China, and Spain. Indeed, many paleontologists believe that the miniaturized hominins from the island of Flores off Indonesia were similarly left over from one of these early Pleistocene diasporas. As far as we know, all of these early-dispersing populations eventually died out. However, a branch of Homo erectus remained in tropical Africa and continued to evolve there. All humans today descend from this enduring African branch of Homo erectus, which some paleontologists regard as a separate species, Homo ergaster. Whatever we call them, these larger-brained African hominins were our ancestors, giving rise around 200,000 years ago to even-larger-brained Homo sapiens. Sometime afterward, between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago, these anatomically modern humans spread out of Africa, and Homo sapiens began its extraordinary expansion around the world.[47]

So here we have a footloose hominin that managed to persist—albeit initially just barely—for 1.6 million years, eight times longer than Homo sapiens has been on this earth. Yet there were probably never very many of them. Unlike the case of other large mammals traversing savannas and mixed woodland-savanna habitats a million years ago, it takes tremendous effort and considerable luck to find even a single skull belonging to the African branch of Homo erectus. My guess is that one reason for the scarcity of such finds is that the creatures themselves were scarce. It was probably not until 80,000 or so years ago in Africa, and perhaps 50,000 years ago in Europe, that human populations began to expand. Prior to that, Paleolithic populations would have been small and dispersed. In total, they would have numbered in the tens of thousands, and the resources they needed would often have been widely distributed as well as unpredictable.[48] When vegetable food or game were available, luck, skill, and the effort expended to harvest them would have mattered more than fighting for them.

Without kin and as-if kin to help protect and especially to help provision them, few Pleistocene children could have survived into adulthood. The fact that children depend so much on food acquired by others is one reason why those seeking human universals would do well to begin with sharing. Nevertheless, in Darwinian circles these days the most widely invoked explanation for how humans became so hypersocial is to stress how helpful within-group cooperation is when defending against or wiping out competing groups. We are told again and again that “the human ability to generate in-group amity often goes hand in hand with out-group enmity.”[49] Such generalizations are probably accurate enough for humans where groups are in competition with one another for resources, but how much sense would it have made for our Pleistocene ancestors eking out a living in the woodland and savannas of tropical Africa to fight with neighboring groups rather than just moving?

Small bands of hunter-gatherers, numbering 25 or so individuals, under conditions of chronic climatic fluctuation, widely dispersed over large areas, unable to fall back on staple foods like sweet potatoes or manioc as some modern foragers in New Guinea or South America do today, would have suffered from high rates of mortality, particularly child mortality, due to starvation as well as predation and disease. Recurring population crashes and bottlenecks were likely, resulting in difficulty recruiting sufficient numbers. Far from being competitors for resources, nearby members of their own species would have been more valuable as potential sharing partners. When conflicts did loom, moving on would have been more practical as well as less risky than fighting.[50]

Nevertheless, from the early days of evolutionary anthropology to today’s textbooks in evolutionary psychology, the tendency has been to devote more space to aggression and our “killer instincts” or to emphasize “demonic” chimpanzeelike tendencies for males to join with other males in their group to hunt neighboring groups and intimidate, beat, torture, and kill them.[51] No doubt our Pleistocene ancestors experienced jealousy, competed for reputation, and harbored grudges or desires for retribution that occasionally escalated into mayhem. Homicides among hunter-gatherers are well documented, often crimes of passion involving women. But such killings tend to involve individuals who know each other rather than warfare between adjacent groups. In spite of abundant evidence documenting intergroup conflict over the past 10,000 to 15,000 years, there is no evidence of warfare in the Pleistocene. Such absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, but it helps to explain why many of those who actually study hunter-gatherers are skeptical about projecting the bellicose behavior of post-Neolithic peoples back onto roaming kin-based bands of hunter-gatherers, and why some anthropologists refer to the Pleistocene as the “period of Paleolithic warlessness.”[52]

I am not about to argue that competition is unimportant. We are primates, after all. But what worries me is that by focusing on intergroup competition, we have been led to overlook factors such as childrearing that are at least as important (in my opinion, even more important) for explaining the early origins of humankind’s peculiarly hypersocial tendencies. We have underestimated just how important shared care and provisioning of offspring by group members other than parents have been in shaping prosocial impulses.

I am assuming that prior to the Neolithic, when around 12,000 or so years ago people began to settle down and produce rather than just gather food, band-level societies would have gone to the same lengths to avoid outright conflicts and to maintain harmonious relations as do the African hunter-gatherers studied by twentieth and twenty-first century ethnographers. Acutely aware of how divisive and potentially dangerous status-striving and self-aggrandizing tendencies can be, hunter-gatherers almost everywhere are known for being fiercely egalitarian and going to great lengths to downplay competition and forestall ruptures in the social fabric, for reflexively shunning, humiliating, even ostracizing or executing those who behave in stingy, boastful, or antisocial ways.[53]

When murder does occur, group members intervene and customs are invoked that help keep violent apelike instincts from escalating and to prevent homicides from spiraling into wider blood feuds or intergroup fighting.[54] People living in band-level gathering and hunting societies behave as if they understand that their survival and that of their children depend on others, that without kin and as-if kin to help keep children safe and fed, their communities cannot survive. Maintaining social contacts and exchanging goods and services, even with those who are not particularly close relatives, is something humans are emotionally and temperamentally peculiarly well equipped to do, especially when compared with other apes.

Yet textbooks in fields like evolutionary psychology devote far more space to aggression, or to how men and women competed for or appealed to mates, than they do to how much early humans shared with one another to jointly rear offspring.[55] Even when human hypersociality is noted, explanations tend to emphasize between-group competition rather than how difficult it was to ensure the survival to breeding age of costly, slow-maturing children. Yet as this book will make clear, without shared care and provisioning, all that inter- and intragroup strategizing and strife would have been—evolutionarily speaking—just so many grunts and contortions signifying nothing.

Pan-Human Comparisons

The Great Apes known as common chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) lack the giving impulses typical of people. Reflexively xenophobic, either sex is more likely to attack than to tolerate a stranger of the same sex. However, members of another Great Ape species, bonobos (Pan paniscus, sometimes called pygmy chimpanzees), are more tolerant and relaxed around conspecifics. Bonobos are temperamentally more similar to humans in this respect than common chimpanzees are. Genetically, however, neither species of chimpanzee is closer to humans than the other is. Humans shared a common ancestor with these other two apes six or so million years ago.

Although genetically equidistant from humans, the two species of the genus Pan diverged from each other only in the past two million years. No one knows whether bonobos derived from a more chimpanzeelike ancestor or the other way around. Yet because Pan troglodytes has been intensively studied for much longer than Pan paniscus, and also because their dominance-oriented and aggressive behavior, including murderous raids on neighboring groups, more nearly conforms to widely accepted stereotypes about human nature, there is a bias toward viewing common chimpanzees as the template for the genus, while dismissing bonobos as some eccentric offshoot. As a result, the violence-prone temperament assigned to male Pan troglodytes is routinely projected back onto our Paleolithic ancestors.[56]

Even though no one knows whether common chimpanzees or bonobos provide the better model for reconstructing particular traits among our hominin ancestors, if I had to bet on which species made the more plausible candidate for reconstructing a line of apes with the potential to evolve extensive sharing, particularly care and provisioning of young by group members other than parents (known as alloparents),{1} I would bet on bonobos. Based on laboratory experiments, bonobos appear to be more gregarious, and bonobo females in particular are temperamentally better suited to tolerate others and to learn to coordinate their behavior with them.[57] In the wild as well as in captivity, bonobos tend to be more peaceful and sociable than common chimpanzees. Thus far, bonobos have not been observed to stalk or kill neighbors, although we know too little to say they never do. What we do know is that when bonobo communities meet at the border of their home ranges or when strange males try to immigrate into a group, the responses vary with the circumstances. Individuals may exhibit hostility or they may intermingle peaceably. Males and females may even consort with one another.[58] Opportunistic copulations with strangers are facilitated because female bonobos are nearly continuously sexually receptive and exhibit red sexual swellings during most days of their estrous cycles, with no specific visual advertisement at ovulation.[59]

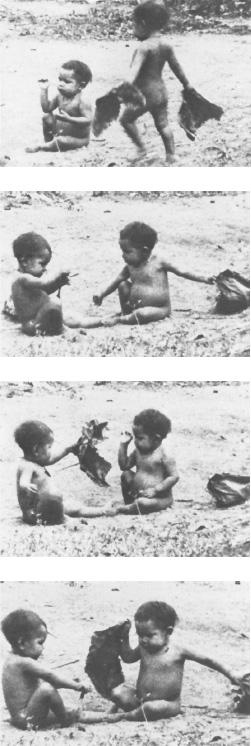

Both in captivity and in the wild, bonobos share more readily than chimpanzees do, and when begged by youngsters, group members of both sexes may provide food to the offspring of their female friends.[60] In general, bonobos seem more eager to cooperate and may be more adept at reconciliation after conflict.[61] They nimbly and routinely combine vocalizations, facial expressions, and gestures for effective, flexible communication.[62] Yet bonobos rarely exhibit the spontaneous giving impulses commonly observed in very young human children.

Among people, these giving impulses, combined with chimpanzees’ and the other Great Apes’ rudimentary capacity for attributing mental states and feelings to others, lead humans of all ages to routinely seek out opportunities to engage with other individuals. The kind of interindividual tolerance so typical of humans suggests that even before people had language to discuss things, prehuman or early human apes were equipped with the capacity to identify with others and engage with them in ways that avoided fights.[63] These hominins were already emotionally different from other apes. This is where the homology between humans and “demonic” chimpanzees breaks down. In what follows I will argue that as long as a million and a half years ago, the African ancestors of Homo sapiens were already emotionally very different from the ancestors of any other extant ape, already more like the sort of ape one would prefer to travel with in a confined space.

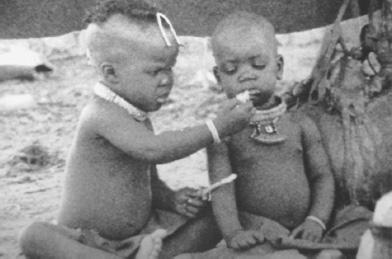

Giving Impulses

A human child is born eager to connect with others. In a gathering and hunting society, that child also would become accustomed to being cared for and fed by others in a nurturing environment.[64] Before Ju/’hoansi children are a year old and able to talk, they are already socialized to share with their mother and with other people as well. Among the first words a child learns are na (“Give it to me”) and i (“Here, take this”).[65] Polly Wiessner recalls an old woman cutting off a strand of ostrich eggshell beads from around her grandchild’s neck, washing the beads off, and then placing them in the child’s hand to present (however grudgingly) to a relative. After the lesson of giving was accomplished, the child was given new beads. This routine was repeated until, by about age nine, children themselves initiated giving. By adolescence, a fully socialized donor expands his or her hxaro contacts further and further afield. The fearful prospect of disrupting the fabric of relationships that sustained the lives of our ancestors acted as a perpetual lid, constraining conflict.

Among nonhuman apes, however, sharing is uncommon, neither spontaneous nor reciprocal. An alpha male chimpanzee grasping the carcass of a monkey he just killed may allow a sexually receptive female or close male associate to rip off a piece, but this is more like “tolerated theft” than a real gift.[66] Rarely have fieldworkers seen a wild chimpanzee extend a preferred section of meat, even to his best ally. Yet humans routinely offer preferred foods to others—the best hospitality we can possibly provide. A mother chimpanzee or orangutan will tolerate her youngster taking a desirable scrap of the food she is eating, but she rarely takes the initiative in offering it. If a Pan troglodytes mother does extend her hand with a tidbit, she will most likely proffer a stem or some other unpalatable plant part that she herself does not particularly want to eat.

Although bonobos may be more tolerant about food sharing than common chimpanzees, no one would mistake their behavior for gift-giving. The majority of sharing involves plant foods rather than meat and usually occurs between two adult females or an adult female and an infant—her own or the infant of one of her female allies or associates. Instead of being offered some delectable treat, infants merely have license to take food in the possession of allomothers. When an adult bonobo shares food with another adult, almost invariably the offer is in reaction to begging gestures similar to those infants make.[67] Not long ago, at a bonobo study site in the Congo called Lomako, researchers watched as females gathered to feed on the corpse of a duiker. Among common chimpanzees, males are dominant over females and control access to meat; but among bonobos, females are dominant to males and control the flow of food. On this particular occasion, all three infants present could pick at the carcass and were also permitted to casually take pieces of meat from the hands and mouths of adults, but this is as generous as things got.[68]

Where gift-giving does occur in the animal world, it tends to be a highly ritualized, instinctive affair, as when a male scorpion fly offers prey to a prospective mate as a “nuptial gift” to induce the female to mate with him, or when male bowerbirds or flightless cormorants bring some eye-catching object to a fertile female to use in decorating her nest. Cases of nonhuman animals voluntarily offering a preferred food in the true spirit of gift-giving are rare, except in species which, like humans, also have deep evolutionary histories of what I call cooperative breeding, where there is shared care and provisioning of young.[69]

Among the higher primates, humans stand out for their chronic readiness to exchange small favors and give gifts. Donors often take the initiative, actually seeking opportunities and expending inordinate thought and effort to select “just the right gift,” the one most likely to suit the occasion or to impress or appeal to the recipient. Humans spontaneously notice and keep track of the smallest detail about their exchanges.[70] Custom, language, and personal experiences shape the specifics, but the urge to share is hard-wired, and neurophysiologists are getting to the point where they can actually monitor, if still only crudely, the pleasure humans derive from being generous, helping, and sharing.[71]

This should not come as a surprise. As early as a million years ago, archaeologists tell us, hominins were transferring materials between distant sites. By the Middle Stone Age (50,000 to 130,000 years ago), the type and quantity of such transfers indicates the existence of long-distance exchange networks.[72] We can say with considerable confidence that the sharing of material objects, and with it a degree of intersubjectivity that would make such sharing a satisfying activity, go far back in time. Yet as universal and presumably ancient in the hominin line as sharing appears to be, a comparable giving impulse is not present in other apes. Whereas competitiveness and aggression are fairly easy to understand, generosity is both less common and more interesting, but from an evolutionary perspective far harder to explain.

How Could Humans Become Such Cooperative Apes?

The archaeological record over the past 10,000 years, and especially the historical record of the past few millennia, abounds with ruined abodes, smashed skulls, and skeletons penetrated by arrowheads. Beautifully colored murals from ancient Mexico and other locales depict the grisly torture of captured enemies, fearsome and totally convincing war propaganda from the distant past. Such evidence renders a bloody-awful record bloody clear. Yet selfish genes and violent predispositions notwithstanding, it takes high population densities, competition for the same resources, long-standing conflicts of interest, and major provocations (often filtered through virulent ideologies and rabble-rousing propaganda) to persuade human apes that neighboring people are sufficiently alien, evil, and potentially dangerous to warrant face-to-face killing and the risks associated with trying to wipe out another group.[73]

One of the most dangerous things that could ever happen to a common chimpanzee would be to find himself suddenly introduced to another group of chimpanzees. A stranger risks immediate attack by the group’s same-sex members. Now think back to Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Bahamian Islands, his first landfall in the New World. To greet his ship, out came Arawak islanders, swimming and paddling canoes, unarmed and eager to greet the newcomers. Lacking a common language, they proceeded to proffer food and water, as well as gifts of parrots, balls of cotton, and fishing spears made from cane. Something similar may have happened to Captain Cook on his arrival in the Hawaiian islands. “The very instant I leaped ashore,” wrote Cook, the local people “brought me a great many small pigs and gave us without regarding whether they got anything in return.”[74]

European sailors were amazed by such spontaneous generosity, although Christopher Columbus simply found the Arawak naive. Columbus’s description of first contact parallels those of Westerners with the Bushmen and other pre-Neolithic peoples: “When you ask for something they have, they never say no. To the contrary, they offer to share with anyone.” But Columbus, himself the product of Europe’s long post-Neolithic traditions, had different ideas: “They do not bear arms, and do not know them, for I showed them a sword . . . and [they] cut themselves out of ignorance,” the explorer noted in his log. “They would make fine servants . . . With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.”

Examples abound of individuals from highly stratified, dominance-oriented, aggressive societies expanding at the expense of people from more egalitarian and group-oriented traditions, people who stockpile social obligations rather than amass things. Alas, it is far easier to imagine the Arawak becoming more like Columbus than the other way around. Only with more reliable food sources from unusually rich coastal or freshwater habitats or with food surpluses from horticulture or herding would higher population densities and increasingly stratified societies become possible, along with the need to protect such resources. As groups grow larger, less personalized, and more formally organized, they would also be prone to shift from occasional violent disagreements between individuals to the groupwide aggression that we mistakenly take for granted as representative of humankind’s naturally warlike state.[75]

Although it is unclear just how much fighting and mayhem went on among our Pleistocene ancestors (it probably varied a lot with local circumstances) or just when organized warfare first appeared, what is clear is that once local conditions promote the emergence of warlike societies, that way of life (as well as the genes of those who excel at it) will spread.[76] Altruists eager to cooperate fare poorly in encounters with egocentric marauders.[77] So this is the puzzle: How was it possible that the more empathic and generous types of hunter-gatherers developed, much less ever flourished, in ancient African landscapes occupied by highly self-centered apes?

This is a profoundly relevant question. Were it not for the peculiar combination of empathy and mind reading, we would not have evolved to be humans at all. This poor teeming planet of ours would be under the thrall of one of the other ten or so branches of the genus Homo, populated by some alternate variation on the themes of bipedal hunting apes with large brains, elaborate tool kits, and an omnivorous diet who entered the fray over the preceding two million years. Without the capacity to put ourselves cognitively and emotionally in someone else’s shoes, to feel what they feel, to be interested in their fears and motives, longings, griefs, vanities, and other details of their existence, without this mixture of curiosity about and emotional identification with others, a combination that adds up to mutual understanding and sometimes even compassion, Homo sapiens would never have evolved at all.[78] The niches humans occupy would have been filled by very different apes. This is where intersubjectivity comes in. But what was the impetus? Given the ecological circumstances of early hominin populations, do we really want to rely on out-group hostility and reflexively genocidal urges as the explanation of choice for the emergence of peculiarly prosocial natures?

According to the best available genetic reconstructions of our own species, the founding population of anatomically modern humans who left Africa some time after 100,000 years ago numbered 10,000 or fewer breeding adults, a rag-tag bunch preoccupied with keeping themselves and their slow-maturing children alive. The chimpanzee genome today is more diverse than that of humans probably because these once highly successful and widespread creatures descended from a more diverse and numerous founding stock than modern humans did.[79] These days, chimpanzees are in far more immediate danger of extinction than are humans, but 50,000 to 70,000 years ago the situation was reversed. Only barely, by the skin of their teeth, did the original population of Homo sapiens avoid the same fate—extinction—suffered by all the other hominins.

Apart from periodic increases in unusually rich locales, most Pleistocene humans lived at low population densities.[80] The emergence of human mind reading and gift-giving almost certainly preceded the geographic spread of a species whose numbers did not begin to really expand until the past 70,000 years. With increasing population density (made possible only, I would argue, because they were already good at cooperating), growing pressure on resources, and social stratification, there is little doubt that groups with greater internal cohesion would prevail over less cooperative groups. But what was the initial payoff? How could hypersocial apes evolve in the first place?

As Tomasello argues, the capacity to be far more interested in and responsive to others’ mental states was the critical trait that emerged and set the ancestors of humans apart from other nonhuman apes. Capacities for learning from each other and sophisticated cooperation that flowed from enhanced mind reading led to unprecedented advances in the realm of culture and, with cumulative cultural knowledge, in technology—gradual advances that eventually took on a life of their own. As a consequence, humans were able to prosper, develop networks of exchange to survive where otherwise they could not, and eventually to spread around the globe. The rest is history—as well as our species’ best hope for having a future. But recognizing this unusual human capacity for caring about what others think, feel, and intend begs the question: How did it happen that cognitive and emotional traits with such obvious benefits for enhancing survival came to characterize only this single surviving line of apes? How could natural selection ever have favored the peculiarly empathic qualities that over the course of human evolution have served our species of emotionally modern humans so well?

Natural selection has no way to foresee eventual benefits. Future payoffs cannot be used to explain the initial impetus, that is, the origin of mind reading. I don’t doubt (as book after book describing “human nature and the origins of war” remind us) that “a high level of fellow feeling makes us better able to unite to destroy outsiders.”[81] But if hypersociality helps one group beat out another, would not in-group cooperation in the service of out-group competition have served other apes (for example, warring communities of chimpanzees) just as well? Indeed, we already know that chimpanzees perform best on tests requiring a rudimentary theory of mind when they are in competitive situations.[82]

When I confided these theoretical difficulties to Polly Wiessner, she acknowledged worrying about the same problem. This expert on hunter-gatherer social relations, who as it happens was raised in Vermont, proceeded to recount the following anecdote about a lost tourist asking directions from a local: “If I were aiming to go there,” replied the crotchety New Englander, “I would not start out from here.”[83] There it was, my problem in a nutshell. Starting out with an ape as self-centered and competitive as a chimpanzee, how could natural selection ever have favored the aptitudes and quirks of mind that underpin the high levels of cooperation found in humans? How could Mother Nature concoct such a hypersocial ape starting with such an impulsively selfish one? The answer, as we will see, is that she didn’t start from there.

This Book

Mothers and Others is about the emergence of a particular mode of childrearing known as “cooperative breeding” and its psychological implications for apes in the line leading to Homo sapiens. As defined by sociobiologists and discussed in a rich empirical and theoretical literature, “cooperative breeding” refers to any species with alloparental assistance in both the care and provisioning of young. I will propose that a long, long time ago, at some unknown point in our evolutionary history but before the evolution of 1,350 cc sapient brains (the hallmark of anatomically modern humans) and before such distinctively human traits as language (the hallmark of behaviorally modern humans), there emerged in Africa a line of apes that began to be interested in the mental and subjective lives—the thoughts and feelings—of others, interested in understanding them. These apes were markedly different from the common ancestors they shared with chimpanzees, and in this respect they were already emotionally modern.

As in all apes, the successful rearing of their young was a challenge. Mortality rates from predation, accidents, disease, and starvation were staggeringly high and weighed most heavily on the young, especially children just after weaning. Of the five or so offspring a woman might bear in her lifetime, more than half—and sometimes all—were likely to die before puberty. Unlike mothers among other African apes, who nurtured infants on their own, these early hominin mothers relied on groupmates to help protect, care for, and provision their unusually slow-maturing children and keep them on the survivable side of starvation.

Cooperative breeding does not mean that group members are necessarily or always cooperative. Indeed, as we will see, competition and coercion can be rampant. But in the case of early hominins, alloparental care and provisioning set the stage for infants to develop in new ways. They were born into the world on vastly different terms from other apes. It takes on the order of 13 million calories to rear a modern human from birth to maturity, and the young of these early hominins would also have been very costly. Unlike other ape youngsters, they would have depended on nutritional subsidies from caregivers long after they were weaned.[84]

Years before a mother’s previous children were self-sufficient, she would give birth to another infant, and the care these dependent youngsters required would be far in excess of what a foraging mother by herself could regularly supply. Both before birth and especially afterward, the mother needed help from others; and even more importantly, her infant would need to be able to monitor and assess the intentions of both his mother and these others and to attract their attentions and elicit their assistance in ways no ape had ever needed to do before. For only by eliciting nurture from others as well as his mother could one of these little humans hope to stay safe and fed and to survive.