Chapter 5: Utilitarianism — The Greatest Good

Introduction

“On the Principle of Utility” introduces Bentham’s theory of consequentialism, which bases the moral worth of a given action/inaction on its consequent outcome. From this theoretical bedrock, Bentham advances his principle of utility, one that fixes moral obligation to the promotion of pleasure and the mitigation of pain (Bentham 2017).

The hedonic calculus (or felicific calculous) signifies Bentham’s methodological framework that measures and compares the utility of different actions by quantifying associated pleasures and pains. As you will see below, this calculous involves several criteria — intensity, duration, certainty, propinquity, fecundity, and purity — to evaluate which outcomes are most likely to maximize overall happiness and minimize overall suffering (Bentham 2017).

Importantly, Bentham’s principle of utility serves as a common framework for moral assessment and decision-making that has been applied to a range of individual, social, and governmental domains, with the overarching objective of optimizing collective being (Bentham 2017).

– CALUM MCCRACKEN

Reading 1: Jeremy Bentham — “Utilitarianism”

Chapter I

I. Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do. On the one hand the standard of right and wrong, on the other the chain of causes and effects, are fastened to their throne. They govern us in all we do, in all we say, in all we think: every effort we can make to throw off our subjection, will serve but to demonstrate and confirm it. In words a man may pretend to abjure their empire: but in reality he will remain subject to it all the while. The principle of utility [1] recognizes this subjection, and assumes it for the foundation of that system, the object of which is to rear the fabric of felicity by the hands of reason and of law. Systems which attempt to question it, deal in sounds instead of sense, in caprice instead of reason, in darkness instead of light.

But enough of metaphor and declamation: it is not by such means that moral science is to be improved.

II. The principle of utility is the foundation of the present work: it will be proper therefore at the outset to give an explicit and determinate account of what is meant by it. By the principle [2] of utility is meant that principle which approves or disapproves of every action whatsoever. according to the tendency it appears to have to augment or diminish the happiness of the party whose interest is in question: or, what is the same thing in other words to promote or to oppose that happiness. I say of every action whatsoever, and therefore not only of every action of a private individual, but of every measure of government.

III. By utility is meant that property in any object, whereby it tends to produce benefit, advantage, pleasure, good, or happiness, (all this in the present case comes to the same thing) or (what comes again to the same thing) to prevent the happening of mischief, pain, evil, or unhappiness to the party whose interest [3] is considered: if that party be the community in general, then the happiness of the community: if a particular individual, then the happiness of that individual.

. . .

Chapter IV

I. Pleasures then, and the avoidance of pains, are the ends that the legislator has in view; it behoves him therefore to understand their value. Pleasures and pains are the instruments he has to work with: it behoves him therefore to understand their force, which is again, in other words, their value.

II. To a person considered by himself, the value of a pleasure or pain considered by itself, will be greater or less, according to the four following circumstances:

- Its intensity.

- Its duration.

- Its certainty or uncertainty.

- Its propinquity or remoteness.

III. These are the circumstances which are to be considered in estimating a pleasure or a pain considered each of them by itself. But when the value of any pleasure or pain is considered for the purpose of estimating the tendency of any act by which it is produced, there are two other circumstances to be taken into the account; these are,

- Its fecundity, or the chance it has of being followed by sensations of the same kind: that is, pleasures, if it be a pleasure: pains, if it be a pain.

- Its purity, or the chance it has of not being followed by sensations of the opposite kind: that is, pains, if it be a pleasure: pleasures, if it be a pain.

These two last, however, are in strictness scarcely to be deemed properties of the pleasure or the pain itself; they are not, therefore, in strictness to be taken into the account of the value of that pleasure or that pain. They are in strictness to be deemed properties only of the act, or other event, by which such pleasure or pain has been produced; and accordingly are only to be taken into the account of the tendency of such act or such event.

IV. To a number of persons, with reference to each of whom to the value of a pleasure or a pain is considered, it will be greater or less, according to seven circumstances: to wit, the six preceding ones; viz.,

- Its intensity.

- Its duration.

- Its certainty or uncertainty.

- Its propinquity or remoteness.

- Its fecundity.

- Its purity.

And one other; to wit:

- Its extent; that is, the number of persons to whom it extends; or (in other words) who are affected by it.

V. To take an exact account then of the general tendency of any act, by which the interests of a community are affected, proceed as follows. Begin with any one person of those whose interests seem most immediately to be affected by it: and take an account,

- Of the value of each distinguishable pleasure which appears to be produced by it in the first instance.

- Of the value of each pain which appears to be produced by it in the first instance.

- Of the value of each pleasure which appears to be produced by it after the first. This constitutes the fecundity of the first pleasure and the impurity of the first pain.

- Of the value of each pain which appears to be produced by it after the first. This constitutes the fecundity of the first pain, and the impurity of the first pleasure.

- Sum up all the values of all the pleasures on the one side, and those of all the pains on the other. The balance, if it be on the side of pleasure, will give the good tendency of the act upon the whole, with respect to the interests of that individual person; if on the side of pain, the bad tendency of it upon the whole.

- Take an account of the number of persons whose interests appear to be concerned; and repeat the above process with respect to each. Sum up the numbers expressive of the degrees of good tendency, which the act has, with respect to each individual, in regard to whom the tendency of it is good upon the whole: do this again with respect to each individual, in regard to whom the tendency of it is good upon the whole: do this again with respect to each individual, in regard to whom the tendency of it is bad upon the whole. Take the balance which if on the side of pleasure, will give the general good tendency of the act, with respect to the total number or community of individuals concerned; if on the side of pain, the general evil tendency, with respect to the same community.

VI. It is not to be expected that this process should be strictly pursued previously to every moral judgment, or to every legislative or judicial operation. It may, however, be always kept in view: and as near as the process actually pursued on these occasions approaches to it, so near will such process approach to the character of an exact one.

VII. The same process is alike applicable to pleasure and pain, in whatever shape they appear: and by whatever denomination they are distinguished: to pleasure, whether it be called good (which is properly the cause or instrument of pleasure) or profit (which is distant pleasure, or the cause or instrument of, distant pleasure,) or convenience, or advantage, benefit, emolument, happiness, and so forth: to pain, whether it be called evil, (which corresponds to good) or mischief, or inconvenience or disadvantage, or loss, or unhappiness, and so forth.

VIII. Nor is this a novel and unwarranted, any more than it is a useless theory. In all this there is nothing but what the practice of mankind, wheresoever they have a clear view of their own interest, is perfectly conformable to. An article of property, an estate in land, for instance, is valuable, on what account? On account of the pleasures of all kinds which it enables a man to produce, and what comes to the same thing the pains of all kinds which it enables him to avert. But the value of such an article of property is universally understood to rise or fall according to the length or shortness of the time which a man has in it: the certainty or uncertainty of its coming into possession: and the nearness or remoteness of the time at which, if at all, it is to come into possession. As to the intensity of the pleasures which a man may derive from it, this is never thought of, because it depends upon the use which each particular person may come to make of it; which cannot be estimated till the particular pleasures he may come to derive from it, or the particular pains he may come to exclude by means of it, are brought to view. For the same reason, neither does he think of the fecundity or purity of those pleasures. Thus much for pleasure and pain, happiness and unhappiness, in general. We come now to consider the several particular kinds of pain and pleasure. . . .

Unless otherwise noted, “Jeremy Bentham – On the Principle of Utility” by Jeremy Bentham (2017) in The Originals: Classic Readings in Western Philosophy [edited by Jeff McLaughlin] is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

This is an abridged version of Classical Utilitarianism by Jeremy Bentham, edited by Jeff McLaughlin. The original work is in the public domain and available via Pressbooks:https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/classicreadings/chapter/jeremy-bentham-on-the-principle-of-utility/. Abridgment and adaptation by Grace Boehm, 2025.

Contemporary Language Edition

Reading 2: John Stuart Mill — “Utilitarianism Refined”

Utilitarianism

…The creed which accepts as the foundation of morals, Utility, or the Greatest Happiness Principle, holds that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness. By happiness is intended pleasure, and the absence of pain; by unhappiness, pain, and the privation of pleasure. To give a clear view of the moral standard set up by the theory, much more requires to be said; in particular, what things it includes in the ideas of pain and pleasure; and to what extent this is left an open question. But these supplementary explanations do not affect the theory of life on which this theory of morality is grounded- namely, that pleasure, and freedom from pain, are the only things desirable as ends; and that all desirable things (which are as numerous in the utilitarian as in any other scheme) are desirable either for the pleasure inherent in themselves, or as means to the promotion of pleasure and the prevention of pain.

Now, such a theory of life excites in many minds, and among them in some of the most estimable in feeling and purpose, inveterate dislike. To suppose that life has (as they express it) no higher end than pleasure- no better and nobler object of desire and pursuitthey designate as utterly mean and grovelling; as a doctrine worthy only of swine, to whom the followers of Epicurus were, at a very early period, contemptuously likened; and modern holders of the doctrine are occasionally made the subject of equally polite comparisons by its German, French, and English assailants.

When thus attacked, the Epicureans have always answered, that it is not they, but their accusers, who represent human nature in a degrading light; since the accusation supposes human beings to be capable of no pleasures except those of which swine are capable. If this supposition were true, the charge could not be gainsaid, but would then be no longer an imputation; for if the sources of pleasure were precisely the same to human beings and to swine, the rule of life which is good enough for the one would be good enough for the other. The comparison of the Epicurean life to that of beasts is felt as degrading, precisely because a beast’s pleasures do not satisfy a human being’s conceptions of happiness. Human beings have faculties more elevated than the animal appetites, and when once made conscious of them, do not regard anything as happiness which does not include their gratification. I do not, indeed, consider the Epicureans to have been by any means faultless in drawing out their scheme of consequences from the utilitarian principle. To do this in any sufficient manner, many Stoic, as well as Christian elements require to be included. But there is no known Epicurean theory of life which does not assign to the pleasures of the intellect, of the feelings and imagination, and of the moral sentiments, a much higher value as pleasures than to those of mere sensation. It must be admitted, however, that utilitarian writers in general have placed the superiority of mental over bodily pleasures chiefly in the greater permanency, safety, uncostliness, etc., of the former- that is, in their circumstantial advantages rather than in their intrinsic nature. And on all these points utilitarians have fully proved their case; but they might have taken the other, and, as it may be called, higher ground, with entire consistency. It is quite compatible with the principle of utility to recognise the fact, that some kinds of pleasure are more desirable and more valuable than others. It would be absurd that while, in estimating all other things, quality is considered as well as quantity, the estimation of pleasures should be supposed to depend on quantity alone.

If I am asked, what I mean by difference of quality in pleasures, or what makes one pleasure more valuable than another, merely as a pleasure, except its being greater in amount, there is but one possible answer. Of two pleasures, if there be one to which all or almost all who have experience of both give a decided preference, irrespective of any feeling of moral obligation to prefer it, that is the more desirable pleasure. If one of the two is, by those who are competently acquainted with both, placed so far above the other that they prefer it, even though knowing it to be attended with a greater amount of discontent, and would not resign it for any quantity of the other pleasure which their nature is capable of, we are justified in ascribing to the preferred enjoyment a superiority in quality, so far outweighing quantity as to render it, in comparison, of small account.

Now it is an unquestionable fact that those who are equally acquainted with, and equally capable of appreciating and enjoying, both, do give a most marked preference to the manner of existence which employs their higher faculties. Few human creatures would consent to be changed into any of the lower animals, for a promise of the fullest allowance of a beast’s pleasures; no intelligent human being would consent to be a fool, no instructed person would be an ignoramus, no person of feeling and conscience would be selfish and base, even though they should be persuaded that the fool, the dunce, or the rascal is better satisfied with his lot than they are with theirs. They would not resign what they possess more than he for the most complete satisfaction of all the desires which they have in common with him. If they ever fancy they would, it is only in cases of unhappiness so extreme, that to escape from it they would exchange their lot for almost any other, however undesirable in their own eyes. A being of higher faculties requires more to make him happy, is capable probably of more acute suffering, and certainly accessible to it at more points, than one of an inferior type; but in spite of these liabilities, he can never really wish to sink into what he feels to be a lower grade of existence. We may give what explanation we please of this unwillingness; we may attribute it to pride, a name which is given indiscriminately to some of the most and to some of the least estimable feelings of which mankind are capable: we may refer it to the love of liberty and personal independence, an appeal to which was with the Stoics one of the most effective means for the inculcation of it; to the love of power, or to the love of excitement, both of which do really enter into and contribute to it: but its most appropriate appellation is a sense of dignity, which all human beings possess in one form or other, and in some, though by no means in exact, proportion to their higher faculties, and which is so essential a part of the happiness of those in whom it is strong, that nothing which conflicts with it could be, otherwise than momentarily, an object of desire to them.

Whoever supposes that this preference takes place at a sacrifice of happiness- that the superior being, in anything like equal circumstances, is not happier than the inferior- confounds the two very different ideas, of happiness, and content. It is indisputable that the being whose capacities of enjoyment are low, has the greatest chance of having them fully satisfied; and a highly endowed being will always feel that any happiness which he can look for, as the world is constituted, is imperfect. But he can learn to bear its imperfections, if they are at all bearable; and they will not make him envy the being who is indeed unconscious of the imperfections, but only because he feels not at all the good which those imperfections qualify. It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. And if the fool, or the pig, are of a different opinion, it is because they only know their own side of the question. The other party to the comparison knows both sides.

It may be objected, that many who are capable of the higher pleasures, occasionally, under the influence of temptation, postpone them to the lower. But this is quite compatible with a full appreciation of the intrinsic superiority of the higher. Men often, from infirmity of character, make their election for the nearer good, though they know it to be the less valuable; and this no less when the choice is between two bodily pleasures, than when it is between bodily and mental. They pursue sensual indulgences to the injury of health, though perfectly aware that health is the greater good.

It may be further objected, that many who begin with youthful enthusiasm for everything noble, as they advance in years sink into indolence and selfishness. But I do not believe that those who undergo this very common change, voluntarily choose the lower description of pleasures in preference to the higher. I believe that before they devote themselves exclusively to the one, they have already become incapable of the other. Capacity for the nobler feelings is in most natures a very tender plant, easily killed, not only by hostile influences, but by mere want of sustenance; and in the majority of young persons it speedily dies away if the occupations to which their position in life has devoted them, and the society into which it has thrown them, are not favourable to keeping that higher capacity in exercise. Men lose their high aspirations as they lose their intellectual tastes, because they have not time or opportunity for indulging them; and they addict themselves to inferior pleasures, not because they deliberately prefer them, but because they are either the only ones to which they have access, or the only ones which they are any longer capable of enjoying. It may be questioned whether any one who has remained equally susceptible to both classes of pleasures, ever knowingly and calmly preferred the lower; though many, in all ages, have broken down in an ineffectual attempt to combine both.

From this verdict of the only competent judges, I apprehend there can be no appeal. On a question which is the best worth having of two pleasures, or which of two modes of existence is the most grateful to the feelings, apart from its moral attributes and from its consequences, the judgment of those who are qualified by knowledge of both, or, if they differ, that of the majority among them, must be admitted as final. And there needs be the less hesitation to accept this judgment respecting the quality of pleasures, since there is no other tribunal to be referred to even on the question of quantity. What means are there of determining which is the acutest of two pains, or the intensest of two pleasurable sensations, except the general suffrage of those who are familiar with both? Neither pains nor pleasures are homogeneous, and pain is always heterogeneous with pleasure. What is there to decide whether a particular pleasure is worth purchasing at the cost of a particular pain, except the feelings and judgment of the experienced? When, therefore, those feelings and judgment declare the pleasures derived from the higher faculties to be preferable in kind, apart from the question of intensity, to those of which the animal nature, disjoined from the higher faculties, is suspectible, they are entitled on this subject to the same regard. . . .

This is an abridged version of Utilitarianism Redefined by John Stuart Mill, edited by Jeff McLaughlin. The original work is in the public domain and available via Prressbookshttps://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/classicreadings/chapter/john-stuart-mill-on-utilitarianism/. Abridgment and adaptation by Grace Boehm, 2025.

Contemporary Language Edition

Reading 3: Ursula K. Le Guin — “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas”

Introduction

Let us start our introduction to utilitarianism with an example that shows how utilitarians answer the following question, “Can the ends justify the means?”

Imagine that Peter is an unemployed poor man in New York. Although he has no money, his family still depends on him; his unemployed wife (Sandra) is sick and needs $500 for treatment, and their little children (Ann and Sam) have been thrown out of school because they could not pay tuition fees ($500 for both of them). Peter has no source of income, and he cannot get a loan; even John (his friend and a millionaire) has refused to help him. From his perspective, there are only two alternatives: either he pays by stealing or he does not. So, he steals $1,000 from John in order to pay for Sandra’s treatment and to pay the tuition fees of Ann and Sam. One could say that stealing is morally wrong. Therefore, we will say that what Peter has done — stealing from John — is morally wrong.

Utilitarianism, however, will say what Peter has done is morally right. For utilitarians, stealing in itself is neither bad nor good; what makes it bad or good is the consequences it produces. In our example, Peter stole from one person who has less need for the money and spent the money on three people who have more need for the money. Therefore, for utilitarians, Peter’s stealing from John (the “means”) can be justified by the fact that the money was used for the treatment of Sandra and the tuition fees of Ann and Sam (the “end”). This justification is based on the calculation that the benefits of the theft outweigh the losses caused by the theft. Peter’s act of stealing is morally right because it produces more good than bad. In other words, the action produced more pleasure or happiness than pain or unhappiness; that is, it increased net utility.

The aim of this chapter is to explain why utilitarianism reaches the conclusion described above and then examine the strengths and weaknesses of utilitarianism. The discussion is divided into three parts:

- The first part explains what utilitarianism is.

- The second discusses some varieties (or types) of utilitarianism.

- The third explores whether utilitarianism is persuasive and reasonable.

Further Reading: Frank Aragbonfoh Abumere — “Utilitarianism”

What is Utilitarianism?

Utilitarianism is a form of consequentialism. For consequentialism, the moral rightness or wrongness of an act depends on the consequences it produces. On consequentialist grounds, actions and inactions whose negative consequences outweigh the positive consequences will be deemed morally wrong, while actions and inactions whose positive consequences outweigh the negative consequences will be deemed morally right. On utilitarian grounds, actions and inactions which benefit few people and harm more people will be deemed morally wrong, while actions and inactions which harm fewer people and benefit more people will be deemed morally right.

Benefit and harm utilitarianism can be characterized in more than one way; for classical utilitarians, such as Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) and John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), they are defined in terms of happiness/unhappiness and pleasure/pain. On this view, actions and inactions that cause less pain or unhappiness and more pleasure or happiness than available alternative actions and inactions will be deemed morally right, while actions and inactions that cause more pain or unhappiness and less pleasure or happiness than available alternative actions and inactions will be deemed morally wrong. Although pleasure and happiness can have different meanings, in the context of this chapter, they will be treated as synonymous.

Utilitarians’ concern is how to increase net utility. Their moral theory is based on the principle of utility, which states that “the morally right action is the action that produces the most good” (Driver 2014). The morally wrong action is the one that leads to the reduction of the maximum good. For instance, a utilitarian may argue that although some armed robbers robbed a bank in a heist, as long as there are more people who benefit from the robbery (say, in a Robin Hood-like manner, the robbers generously shared the money with many people) than there are people who suffer from the robbery (say, only the billionaire who owns the bank will bear the cost of the loss), the heist will be morally right rather than morally wrong. And on this utilitarian premise, if more people suffer from the heist while fewer people benefit from it, the heist will be morally wrong.

From the above description of utilitarianism, it is noticeable that utilitarianism is opposed to deontology, which is a moral theory that says that as moral agents, we have certain duties or obligations, and these duties or obligations are formalized in terms of rules (see Kantian Deontology). There is a variant of utilitarianism, namely rule utilitarianism, that provides rules for evaluating the utility of actions and inactions (see the next part of the chapter for a detailed explanation). The difference between a utilitarian rule and a deontological rule is that according to rule utilitarians, acting according to the rule is correct because the rule is one that, if widely accepted and followed, will produce the most good. According to deontologists, whether the consequences of our actions are positive or negative does not determine their moral rightness or moral wrongness. What determines their moral rightness or moral wrongness is whether we act or fail to act in accordance with our duty or duties (where our duty is based on rules that are not themselves justified by the consequences of their being widely accepted and followed).

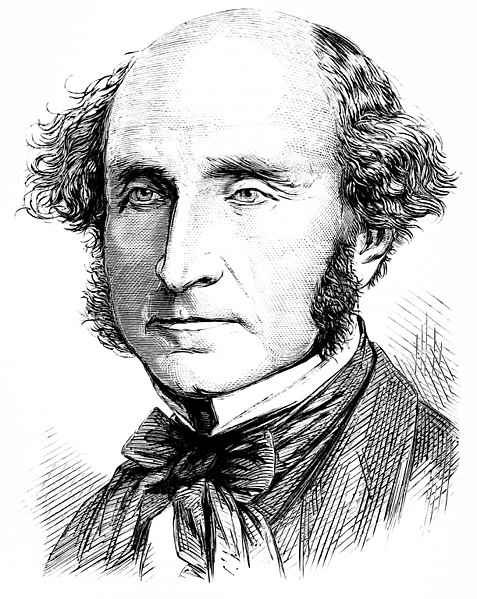

Figure 14.1: “PSM V03 D380 John Stuart Mill” by Unknown Author (1872–1873) [in Popular Science Monthly Volume 3], via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

Some Varieties (Or Types) of Utilitarianism

The above description of utilitarianism is general. We can, however, distinguish between different types of utilitarianism. First, we can distinguish between “actual consequence utilitarians” and “foreseeable consequence utilitarians.” The former base the evaluation of the moral rightness and moral wrongness of actions on the actual consequences of actions, while the latter base the evaluation of the moral rightness and moral wrongness of actions on the foreseeable consequences of actions. J. J. C. Smart (1920–2012) explains the rationale for this distinction with reference to the following example:

Imagine that you rescued someone from drowning. You were acting in good faith to save a drowning person, but it just so happens that the person later became a mass murderer. Since the person became a mass murderer, actual consequence utilitarians would argue that, in hindsight, the act of rescuing the person was morally wrong. However, foreseeable consequence utilitarians would argue that — looking forward (i.e., in foresight) — it could not be foreseen that the person was going to be a mass murderer, hence the act of rescuing them was morally right (Smart 1973, 49). Moreover, they could have turned out to be a “saint” or Nelson Mandela or Martin Luther King Jr., in which case the action would be considered to be morally right by actual consequence utilitarians.

A second distinction we can make is that between act utilitarianism and rule utilitarianism. Act utilitarianism focuses on individual actions and says that we should apply the principle of utility in order to evaluate them. Therefore, act utilitarians argue that among possible actions, the action that produces the most utility would be the morally right action. But this may seem impossible to do in practice, since, for everything that we might do that has a potential effect on other people, we would thus be morally required to examine its consequences and pick the one with the best outcome. Rule utilitarianism responds to this problem by focusing on general types of actions and determining whether they typically lead to good or bad results. For them, this is the meaning of commonly held moral rules: they are generalizations of the typical consequences of our actions. For example, if stealing typically leads to bad consequences, a rule utilitarian would consider stealing in general to be wrong. [4]

Hence, rule utilitarians claim to be able to reinterpret talk of rights, justice, and fair treatment in terms of the principle of utility by claiming that the rationale behind any such rules is really that these rules generally lead to greater welfare for all concerned. We may wonder whether utilitarianism in general is capable of even addressing the notion that people have rights and deserve to be treated justly and fairly because, in critical situations, the rights and well-being of persons can be sacrificed as long as this seems to lead to an increase in overall utility.

For example, in a version of the famous “trolley problem,” imagine that you and an overweight stranger are standing next to each other on a footbridge above a rail track. You discover that there is a runaway trolley rolling down the track and the trolley is about to kill five people who cannot get off of the track quickly enough to avoid the accident. Being willing to sacrifice yourself to save the five persons, you consider jumping off the bridge, in front of the trolley, but you realize that you are far too light to stop the trolley. The only way you can stop the trolley from killing five people is by pushing this large stranger off the footbridge in front of the trolley. If you push the stranger off, he will be killed, but you will save the other five. (Singer 2005, 340)

Utilitarianism, especially act utilitarianism, seems to suggest that the life of the overweight stranger should be sacrificed regardless of any purported right to life he may have. A rule utilitarian, however, may respond that since, in general, killing innocent people to save others is not what typically leads to the best outcomes, we should be very wary of making a decision to do so in this case. This is especially true in this scenario since everything rests on our calculation of what might possibly stop the trolley, while in fact there is really far too much uncertainty in the outcome to warrant such a serious decision. If nothing else, the emphasis placed on general principles by rule utilitarians can serve as a warning not to take too lightly the notion that the ends might justify the means.

Whether or not this response is adequate is something that has been extensively debated with reference to this famous example as well as countless variations. This brings us to our final question here about utilitarianism — whether it is ultimately a persuasive and reasonable approach to morality.

Figure 14.2: “Trams in Christchurch” by Bernard Spragg (2014), via Flickr, is in the public domain.

Is Utilitarianism Persuasive and Reasonable?

First of all, let us start by asking about the principle of utility as the foundational principle of morality, that is, about the claim that what is morally right is just what leads to the better outcome. John Stuart Mill’s argument is based on his claim that “each person, so far as he believes it to be attainable, desires his own happiness” (Mill [1861] 1879, Ch. 4). Mill derives the principle of utility from this claim based on three considerations: desirability, exhaustiveness, and impartiality. That is, happiness is desirable as an end in itself; it is the only thing that is so desirable (exhaustiveness); and no one person’s happiness is really any more desirable or less desirable than that of any other person (impartiality) (see Macleod 2017).

In defending desirability, Mill argues, “The only proof capable of being given that an object is visible, is that people actually see it. The only proof that a sound is audible, is that people hear it: and so of the other sources of our experience. In like manner…the sole evidence it is possible to produce that anything is desirable, is that people do actually desire it.” (Mill [1861] 1879, Ch. 4)

In defending exhaustiveness, Mill does not argue that other things, apart from happiness, are not desired as such. However, while other things appear to be desired, happiness is the only thing that is really desired since whatever else we may desire, we do so because attaining that thing would make us happy. Finally, in defending impartiality, Mill argues that equal amounts of happiness are equally desirable, whether the happiness is felt by the same person or by different persons. In Mill’s words, “each person’s happiness is a good to that person, and the general happiness, therefore, a good to the aggregate of all persons” (Mill [1861] 1879, Ch. 4). We may wonder, however, whether this last argument is truly adequate. Does Mill really show here that we should treat everyone’s happiness as equally worthy of pursuit, or does he simply assert this?

Let us assume that Mill’s argument here is successful and that the principle of utility is the basis of morality. In this case, utilitarianism claims that we should calculate, to the best of our ability, the expected utility that will result from our actions and how it will affect us and others and use that as the basis for the moral evaluation of our decisions. But then we may ask, how exactly do we quantify utility? Here, there are two different but related problems:

- How can we come up with a way of comparing different types of pleasure or pain and benefit or harm that we myself might experience?

- How can we compare one person’s benefit and another’s on some neutral scale of comparison?

Bentham famously claimed that there was a single universal scale that could enable us to objectively compare all benefits and harms based on the following factors: intensity, duration, certainty/uncertainty, proximity, fecundity, purity, and extent. And he offered on this basis what he called a “felicific calculus” as a way of objectively comparing any two pleasures we might encounter (Bentham [1789] 1907).

For example, let us compare the pleasure of drinking a pint of beer to that of reading Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Suppose the following are the case:

- The pleasure derived from drinking a pint of beer is more intense than the pleasure derived from reading Hamlet. — Intensity

- The pleasure of drinking the beer lasts longer than that of reading Hamlet. — Duration

- We are confident that drinking the beer is more pleasurable than reading Hamlet. — Certainty/Uncertainty

- The beer is closer to us than the play, and therefore, it is easier for us to access the former than the latter. — Proximity

- Drinking the beer is more likely to promote more pleasure in the future, while reading Hamlet is less likely to promote more pleasure in the future. — Fecundity

- Drinking the beer is pure pleasure, while reading Hamlet is mixed with something else. — Purity

- Finally, drinking the beer affects both myself and my friends in the bar and so has a greater extent than my solitary reading of Hamlet. — Extent

Since, on all of these measures, drinking a pint of beer is more pleasurable than reading Hamlet, according to Bentham, it follows that it is objectively better for you to drink the pint of beer and forget about reading Hamlet, and so you should. Of course, it is up to each individual to make such a calculation based on the intensity, duration, certainty, etc. of the pleasure resulting from each possible choice they may make in their eyes, but Bentham at least claims that such a comparison is possible.

This brings us back to the problem we mentioned before that, realistically, we cannot be expected to always engage in very difficult calculations every single time we want to make a decision. In an attempt to resolve this problem, utilitarians might claim that in evaluating the moral rightness and moral wrongness of actions, applying the principle of utility can be backward-looking (based on hindsight) or forward-looking (based on foresight). That is, we can use past experience of the results of our actions as a guide to estimating what the probable outcomes of our actions might be and save ourselves from the burden of having to make new estimates for each and every choice we may face.

In addition, we may wonder whether Bentham’s approach misses something important about the different kinds of pleasurable outcomes we may pursue. Mill, for example, would respond to our claim that drinking beer is objectively more pleasurable than reading Hamlet by saying that it overlooks an important distinction between qualitatively different kinds of pleasure. In Mill’s view, Bentham’s calculus misses the fact that not all pleasures are equal — there are “higher” and “lower” pleasures that make it “better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied” (Mill [1861] 1879, Ch. 2). Mill justifies this claim by saying that between two pleasures — although one pleasure requires a greater amount of difficulty to attain than the other pleasure — if those who are competently acquainted with both pleasures prefer (or value) one over the other, then one is a higher pleasure while the other is a lower pleasure.

For Mill, although drinking a pint of beer may seem to be more pleasurable than reading Hamlet, if you are presented with these two options and you are to make a choice — each and every time or as a rule — you should still choose to read Hamlet and forego drinking the pint of beer. Reading Hamlet generates a higher quality (although perhaps a lower quantity) of pleasure, while drinking a pint of beer generates lower quality (although higher quantity) of pleasure.

In the end, these issues may be merely technical problems faced by utilitarianism — is there some neutral scale of comparison between pleasures? If there is, is it based on Betham’s scale, which makes no distinctions between higher and lower pleasures, or Mill’s, which does? However, the more serious problem, remains, which is that utilitarianism seems willing in principle to sacrifice the interests and even perhaps lives of individuals for the sake of the benefit of a larger group. And this seems to conflict with our basic moral intuition that people have a right not to be used in this way. While Mill argued that the notion of rights could be accounted for on purely utilitarian terms, Bentham simply dismissed it. For him such “natural rights” are “simple nonsense, natural and imprescriptible rights, rhetorical nonsense—nonsense upon stilts” (Bentham [1796] 1843, 501).

Conclusion

Let us conclude by revisiting the question we started with: can the ends justify the means? We stated that, as far as utilitarianism is concerned, the answer to this question is in the affirmative. While the answer is plausible and right for utilitarians, it is implausible for many others and notably wrong for deontologists. As we have seen in this chapter, on a close examination, utilitarianism is less persuasive and less reasonable than it appears to be when far away.

Unless otherwise noted, “Utilitarianism” by Frank Araagbonfoh Abumere (2019) in Introduction to Philosophy: Ethics [edited by George Matthews and Christina Hendricks and produced with support from the Rebus Community] is used and adapted under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Bibliography

Bentham, Jeremy. (1789) 1907. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Bentham, Jeremy. (1796) 1843. Anarchical Fallacies. In The Works of Jeremy Bentham, ed. John Bowring. Vol 2. Edinburgh: William Tait.

Driver, Julia. 2014. “The History of Utilitarianism.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2017/entries/utilitarianism-history/.

Hooker, Brad. 2016. “Rule Consequentialism.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/consequentialism-rule/.

Macleod, Christopher. 2017. “John Stuart Mill.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2017/entries/mill/.

Mill, John Stuart. Utilitarianism. (1861) 1879. 7th ed. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/11224.

Singer, Peter. 2005. “Ethics and Intuitions.” The Journal of Ethics 9(3/4): 331-352.

Smart, J. J. C. 1973. “An Outline of a System of Utilitarian Ethics.” In Smart, J. J. C. and Bernard Williams.

Smart, J. J. C. and Bernard Williams. 1973. Utilitarianism: For and Against. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Further Reading

Hare, R. M. 1981. Moral Thinking. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hooker, Brad. 1990. “Rule-Consequentialism.” Mind 99(393): 66-77.

Scheffler, Samuel. 1988. Consequentialism and Its Critics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sen, Amartya and Bernard Williams, eds. 1982. Utilitarianism and Beyond. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sidgwick, Henry. 1907. The Methods of Ethics. London: Macmillan.

Singer, Peter. 2000. Writings on an Ethical Life. New York: HarperCollins.

Smart, J. J. C. and Bernard Williams. 1973. Utilitarianism: For and Against. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thomson, Judith Jarvis. 1985. “The Trolley Problem.” The Yale Law Journal 94(6): 1395-1415.

Williams, Bernard. 1973. “A Critique of Utilitarianism.” In Smart, J. J. C and Bernard Williams.

Discussion Questions

- What is the greatest happiness principle, and on what basis does it determine the rightness of our actions? Do you believe it to be a reliable metric for our moral obligations? Why or why not?

- Are considerations of justice sufficiently integrated into utilitarian theory? Why or why not?

- How practical is Bentham’s hedonic calculous in the real world? For example, what are the implications for public policy?

Thought Experiment

Put this philosophy to the test by checking out the Absurd Trolley Problems web game by Neal Agarwal.

Further Reading

- “Maximizing Morality: The Utilitarian Ethic” by Frank Araagbonfoh Abumere (2019)

https://introductiontoethicsversion2.pressbooks.tru.ca/chapter/maximizing-morality-the-utilitarian-ethic/

Bibliography

Bentham, Jeremey. 2017. “Jeremy Bentham – On the Principle of Utility.” In The Originals: Classic Readings in Western Philosophy, edited by Jeff McLaughlin. Victoria, BC: BCcampus; Kamloops, BC: Thompson River University. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/classicreadings/chapter/jeremy-bentham-on-the-principle-of-utility/.

Stuart Mill, John. 2017. “John Stuart Mill – On Utilitarianism.” In The Originals: Classic Readings in Western Philosophy, edited by Jeff McLaughlin. Victoria, BC: BCcampus; Kamloops, BC: Thompson Rivers University. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/classicreadings/chapter/john-stuart-mill-on-utilitarianism/

How to Cite This Page

McCraken, Calum. 2024. “Utilitarianism.“ In Introduction to Ethics, edited by Jenna Woodrow, Hunter Aiken, and Calum McCracken. Kamloops, BC: TRU Open Press. https://introductiontoethics.pressbooks.tru.ca/chapter/utilitarianism/.

- Greatest happiness or greatest felicity principle: this for shortness, instead of saying at length that principle which states the greatest happiness of all those whose interest is in question, as being the right and proper, and only right and proper and universally desirable, end of human action: of human action in every situation, and in particular in that of a functionary or set of functionaries exercising the powers of Government. The word utility does not so clearly point to the ideas of pleasure and pain as the words happiness and felicity do: nor does it lead us to the consideration of the number, of the interests affected; to the number, as being the circumstance, which contributes, in the largest proportion, to the formation of the standard here in question; the standard of right and wrong, by which alone the propriety of human conduct, in every situation, can with propriety be tried. This want of a sufficiently manifest connexion between the ideas of happiness and pleasure on the one hand, and the idea of utility on the other, I have every now and then found operating, and with but too much efficiency, as a bar to the acceptance, that might otherwise have been given, to this principle. ↵

- The word principle is derived from the Latin principium: which seems to be compounded of the two words primus, first, or chief, and cipium a termination which seems to be derived from capio, to take, as in mancipium, municipium; to which are analogous, auceps, forceps, and others. It is a term of very vague and very extensive signification: it is applied to any thing which is conceived to serve as a foundation or beginning to any series of operations: in some cases, of physical operations; but of mental operations in the present case. The principle here in question may be taken for an act of the mind; a sentiment; a sentiment of approbation; a sentiment which, when applied to an action, approves of its utility, as that quality of it by which the measure of approbation or disapprobation bestowed upon it ought to be governed. ↵

- Interest is one of those words, which not having any superior genus, cannot in the ordinary way be defined. ↵

- Of course, there may be exceptions to such a rule in particular, atypical cases if stealing might lead to better consequences. This raises a complication for rule utilitarians: if they were to argue that we should follow rules such as “do not steal” except in those cases where stealing would lead to better consequences, then this could mean rule utilitarianism wouldn’t be very different from act utilitarianism. One would still have to evaluate the consequences of each particular act to see if one should follow the rule or not. Hooker (2016) argues that rule utilitarianism need not collapse into act utilitarianism in this way, because it would be better to have a set of rules that are more clear and easily understood and followed than ones that require us to evaluate many possible exceptions. ↵